The trio concluded that much more could be said and understood about knowledge, paper, and the gendered worlds that made them. The result was the formation of the Working Group, “Working with Paper: Gendered Practices in the History of Knowledge,” and now a book of the same name, published in June 2019 by the University of Pittsburgh Press.

Image 1. Working Group members during their residency in fall 2016. From left to right: Matthew Eddy, Carla Bittel, Gabriella Szalay, Christine von Oertzen, Dan Bouk, Elizabeth Yale, Elena Serrano, Elaine Leong, Simon Werrett, Anna Maerker. Not present: Jacob Eyferth, Beth Linker, Heather Wolfe. Photo: L. Selle, Berlin.

Working with Paper Constitutes What We Know

As part of the Gender Studies of Science Project within Department II, the group developed a new perspective on how working with paper constitutes what we know. The group’s members came from universities across Europe and the US, and spent four months in residence at the institute from September to December 2016 (Image 1). They participated in a conference and two authors’ workshops, which led to the final product, a volume that breaks new ground in the history of knowledge. The book demonstrates that paper, so ubiquitous that it was often taken for granted, was enmeshed with social conceptions of femininity and masculinity, similarly so pervasive as to be sometimes imperceptible. In doing so, it makes three claims about paper, knowledge, and gender.

Paper Matters beyond the Page

First, the universe of paper and knowledge goes much beyond reading and writing, and the learned practices of a few. In myriad ways, paper matters beyond the page: as a material, a writing substrate, and an object. The book’s chapters consider a wide range of paper materials and objects. Heather Wolfe illustrates how careful folding and sealing of letters mattered as much as what was inscribed on the page (Image 2).

Image 2a: A pleated letter secured with light blue embroidery floss wrapped around the long edge, with a wax seal on the front and back of the packet. This letter has been refolded after the floss had been cut in order to demonstrate what the superscription side of the packet originally looked like. Autograph letter from Jane Skipwith to Lewis Bagot, circa 1610. Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, DC, MS L.a.852.

Image 2b: Detail from a full-page image of the blank panel (the side without the address) of a pleated letter. The letter was secured with pink silk embroidery floss originally wrapped around the fore-edge and the long edge of the packet (now cut) and sealed on both sides. Autograph letter signed from Lady Jane Ashley to Walter Bagot, circa 1609. Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, DC, MS L.a.19.

Elaine Leong considers early modern recipes and reveals how householders, men and women, codified medical knowledge through inscribing, sorting, and pinning together. Simon Werrett uncovers the multiple uses of paper in the eighteenth-century household where French brown paper was used to curl hair (Image 3). Christine von Oertzen shows the true weight of sturdy census cards as they circulated throughout Berlin, and were sorted by housewives in their parlors (Image 4). Anna Maerker demonstrates how paper maché anatomical models served to educate not just medical students, but also edify and reform the workers who assembled the models. As the volume reveals, “paper work” involved multiple practices beyond the page, from folding and sealing letters, to cutting labels and filters, to sorting recipes and data, to burning curls, to mixing paper paste and molding shapes (Image 5). In his afterword, Jacob Eyferth expands this Western spectrum of paper materials and practices by reflecting on the production and uses of bamboo paper in late Imperial China (Image 6).

Image 3.Burning curls with French brown paper. Caricature by Matthew Darly (printer), “Ridiculous Taste or the Ladies Absurdity” (London, 1771). © Trustees of the British Museum, UK.

Image 4. The paper cards used for the processing of data in nineteenth-century Prussian census statistics were mainly sorted and coded by housewives in their parlors. Eduard Nise, Blick in die Wohnstube eines Maurermeisters [Parlor of a master mason], 1891. Watercolor, Inv.Nr. EB 1964, 231 (detail). Courtesy of City Museum for the History of Hamburg, Germany.

Image 5. Molds used in model production of Auzoux’s papier-mâché factory and a model of the male body. Musee de l’Ecorché, Le Neubourg. Photo: A. Maerker.

Image 6. Household paper workshop in Jiajiang, China, ca. 1990. Photo: Jacob Eyferth.

Paper Objects Transcend Boundaries

Second, the book demonstrates that paper objects transcend boundaries and shape epistemic communities, the work, and the people engaging with them. Each contribution takes a particular paper object as a three-dimensional tool and technology. Beth Linker examines how translucent tracing paper, intended for map-making and mechanical engineering, became a medium for “physiological feminism” in the early days of American posture science (Image 7).

Image 7. Photograph of a posture clinic with silhouettes of good and bad posture in the Department of Orthopedics at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, 1926. Courtesy of the Massachusetts General Hospital Archives and Special Collections (subject file Orthopedic Department), Boston, Massachusetts.

Dan Bouk shows how questionnaires used to gather data and the tools to model postwar population research enabled researchers to bridge the spaces between the homes visited during their fieldwork and the “laboratory” space at the research institute (Image 8). Elena Serrano situates eighteenth-century parchment slips inscribed with names and other crucial information attached to the waists of babies as part of a panoptical paper system set up to fight the horrific death rates of Madrid’s foundling house. By following paper—and the tools made from it—into quotidian practices and workflows of knowledge production, the case studies uncover the multilayered conjunctions of paper, doing full justice to the riches that a history of working and knowing with paper has to offer.

Image 8. These paperboard spinning wheels model the United States population in 1930. The top wheel represents data on mortality among white women. Dan Bouk, Abigail Balfour, Erin Burke, and Christy Mills reconstructed these wheels from descriptions in the writings of biomathematician Alfred Lotka. Photo: D. Bouk.

The History of Knowledge is Sociomaterial

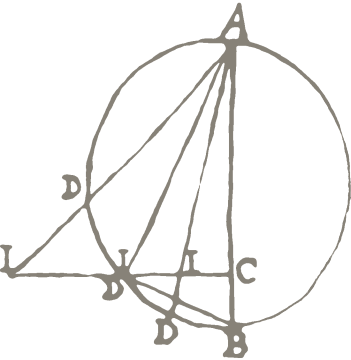

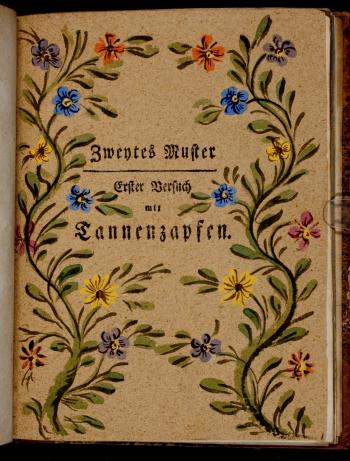

Third, the history of knowledge is a “sociomaterial” one, entangled in the order and disorder of daily life. By focusing on the material, the essays shine light on the women and men, the families and communities who used and manipulated paper. By making paper visible, the volume denaturalizes the social in practices of knowledge production. They analyze the complex worlds in which paper circulates as sets of relationships structured by power and difference. And, they observe how paper moves through the hands of historical actors, producing knowledge as they relate to one another in ways deemed feminine or masculine. Gabriella Szalay makes these negotiations evident through the paper trials of the protestant pastor Jacob Christian Schäffer and his failed attempts to mass produce paper with home-grown substances such as pine cones, poplar wool, or wasps’ nests (Image 9).

Image 9. “Second Sample, First Trial with Pine Cones” from Jacob Christian Schäffer’s paper trials to replace linnen pulp, published in his Neue Versuche und Muster das Pflanzenreich zum Papiermachen und anderen Sachen wirthschaftsnützlich zu gebrauchen (Regensburg: 1767). Realizing that the paper resulting from this trial was too grey and thick to serve as writing paper, Schäffer suggested that it could be used to satisfy the contemporary craze for wall paper. He even appears to have hired a painter to decorate the border of each sample made with this material, as all of the surviving exemplars feature a different pattern. Image courtesy of Universitätsbibliothek Göttingen, Germany.

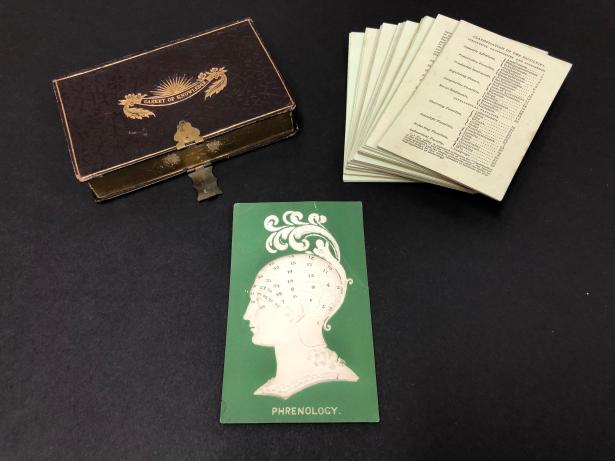

In her narrative, eighteenth-century governance, natural history, experimentation and artisanal expertise coalesced in a potent mix, in which multiple notions of masculinity were equally at stake. In Carla Bittel’s piece, practitioners and consumers of phrenology in Antebellum America used paper charts and cards to assess but also negotiate their own degrees of femininity and masculinity as a way of knowing themselves (Image 10). By moving from analyzing the written to examining the material, and discovering the sociomaterial, we see how paper makes gender more visible and tangible, and in turn how gender relationships bring to light the tactile journeys and life cycles of material things.

Image 10. The “Casket of Knowledge,” including a top card with embossed profile of a phrenological head, and corresponding cards. Mrs. L. Miles, Phrenology and the Moral Influence of Phrenology: Arranged on 40 Cards, Illustrative of the System (London: Ackermann and Co., 1835), History & Special Collections for the Sciences, UCLA Library Special Collections, BF870.P577 1835.

Altogether, the articles in Working with Paper invite readers to enter a universe beyond the page, where paper and gender co-constitute the ways we know. The objects of study (papers and paper stuff) and the methodology (gender analysis) form the grid through which we see knowledge practices unfold in multiple and continual negotiations of power. Such a new perspective emphasizes how knowledge production is inextricable from the order and disorder of the quotidian in which epistemic work is carried out.

About the Editors

Carla Bittel is Associate Professor of History at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles; Elaine Leong led the Minerva Research Group in Department II at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin. In Spring of 2019, she joined the History Department at University College London. Christine von Oertzen is Senior Research Scholar at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science.