Ideals & Practices of Rationality

Twenty-Four Years of the History of Rationality

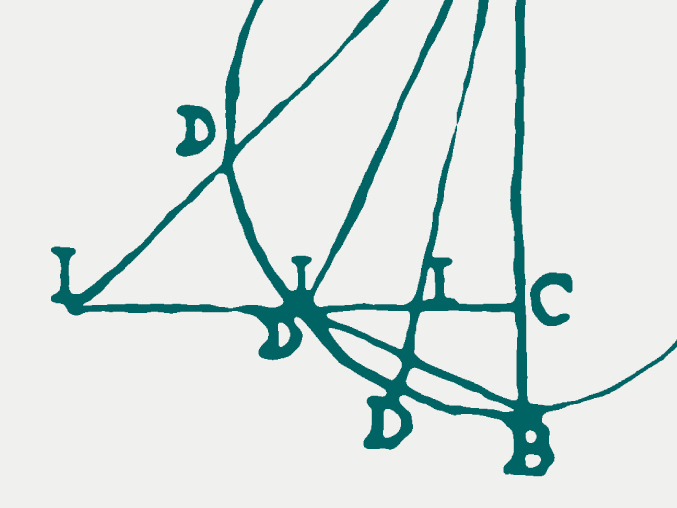

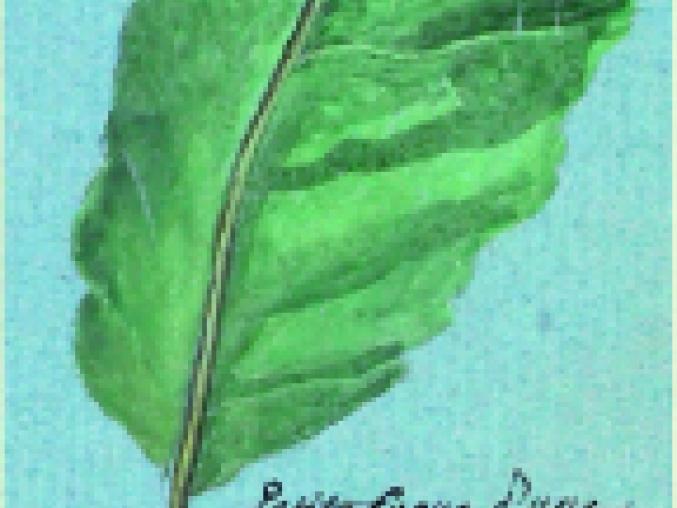

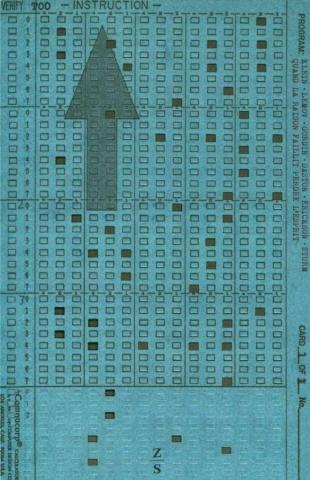

A navigator fixes a course by the stars; a weaver strings a loom with an intricate pattern of colors and shapes; a city official discerns a link between a certain well and the outbreak of an epidemic; a brewer adjusts ingredients to speed up fermentation; a courtier infers a royal intrigue from an exchange of glances; a bureaucrat organizes the tax system of an empire; a herbalist identifies a plant that heals wounds. All of these accomplishments certainly qualify as knowledge, and highly refined knowledge at that, based on close observation, seasoned judgment, and subtle inference. Their accuracy, reliability, and utility are not in doubt; their rationality in matching means to ends is indisputable. But is it the same kind of rationality exemplified in a mathematical demonstration, a precise measurement under controlled laboratory conditions, solving a game-theoretical matrix, making an anatomical image, or constructing the stemma of an ancient text? Is there any common denominator that links all of these rational practices, which cut across divides of head and hand, science and knowledge, the natural and the human sciences?

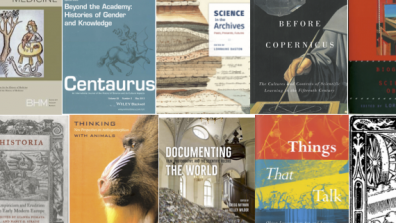

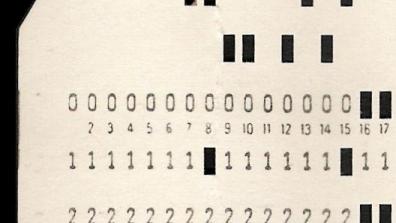

These are the kind of questions that have shaped the research program of Department II since 1995. Dedicated to understanding the “Ideals and Practices of Rationality,” Department II has for the past 24 years probed the forms of rationality using historical, cross-cultural, and cross-disciplinary comparisons. The retirement of Director Lorraine Daston in June 2019 has brought the work of the Department to an end. What have we learned about rationality? The Department’s 22 Working Group volumes and hundreds of individual publications by affiliated scholars provide the best overview of the scope of the Department’s work, which addressed topics as diverse as the moral authority of nature, scientific observation, biographies of scientific objects, Cold War rationality, bureaucratic knowledge, and data histories.