Funding Institutions

Max Planck Society, Minerva Program for the Advancement of Outstanding Female Scientists and Scholars

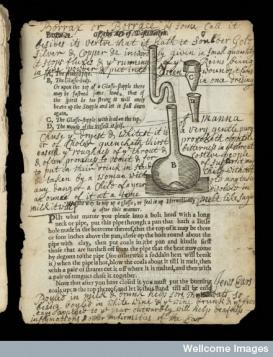

Since the introduction of Gutenberg’s invention of movable type, medical and scientific ideas have circulated in printed books, journals, and pamphlets. Medical print not only allowed academics and medical “professionals” to exchange and discuss new knowledge, but opened access to health-related information for patients and their families. As readers, early modern men and women devoured all sorts of medical texts, from hefty learned tomes to broadsheets advertising wondrous cures, leaving traces of their encounters in book margins, battered leather-bound notebooks and in the flurry of letters sent between friends, families, and acquaintances. These reading “notes” are rarely straightforward copies of existing texts but rather records of particular readers’ appropriation of natural knowledge through processes of information selection, organization, and modification. Within these same pages, our readers also recorded their own first-hand experiences with healing and preserving the human body, their experimentation with drugs and cures, and their observations on nature. As they put pen to paper, their acts of reading become acts of writing; what might at first sight seem to be an act of knowledge transmission becomes an act of knowledge production.

This Research Group investigates how reading and writing practices shaped the codification of medical and natural knowledge in early modern Europe. At the heart of the project is the idea that acts of reading—engagement with new and innovative ideas through printed and handwritten texts—not only profoundly shaped early modern knowledge-making processes but were themselves crucial steps of these processes. It explores the myriad of sites where early modern men and women wrote about health and their inquiries on nature. It traces readers writing on scraps of paper on kitchen tables, scribbling into erasable table books and small vademecums out in the field, and, of course, inscribing notes into the wide margins of the early modern printed book while sitting at a desk. The project focuses on tools long employed by historians of reading, but it is also interested in reconstructing paper archives, analyzing what Anke te Heesen has called “paper technologies,” and examining linguistic practices such as translation and the use and adaptation of contemporary systems of shorthand and ciphers.