Clearly, much training occurs within formal situations such as schools and laboratories. Classrooms and their textbooks have attracted due attention from historians, with a focus in the last decade or so on how teachers convey working knowledge bodily and not only abstractly to their students or apprentices. But learning does not stop with formal education, and often enough it starts elsewhere. Manuals and handbooks have long enabled informal, often self-directed education and training. They also provide a new vantage point for bringing together history of science with history of books and media, from Antiquity to the present. These instructional texts and compendia codify the knowledge of a working community, with an eye to communicating what a new practitioner needs to know. Such texts have also played a key role in bringing local knowledge and know-how to far-flung readers and practitioners around the globe. By following these apparently mundane texts and their uses, rather than focusing only on elite practitioners, we bring into view an exciting new set of historical connections and participants.

Considering a Taken-for-Granted Genre

This project began in Berlin, when Angela Creager was a Visiting Research Scholar in Department II (Ideals and Practices of Rationality, led by Lorraine Daston) at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science (MPIWG) and talking with Mathias Grote from the chair of history of science at Humboldt University about their overlapping interests. They were struck to realize that each of them was writing on the history of a manual, in one case for bacteriology in the early twentieth century, and in the other case for molecular biology in the 1980s. It prompted them to ask: What is a manual? How might we make sense of something so seemingly obvious—instructional literature—that every twentieth-century scientist relies on but nobody really discusses? We quickly realized that the history of what became known as "manuals" and "handbooks" was a complex and entangled one. Eager to excavate and reconstruct a long-range history, we invited Elaine Leong, an early modernist working on recipe literature and histories of reading and writing at the MPIWG, on board. Along with Kerstin von der Krone (Head of Judaica Division, University Library Johann Christian Senckenberg Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main), we co-organized a conference on this theme held at Princeton in June 2018 and supported by the German Historical Institute Washington. From papers on a wide array of handbooks and manuals in the history of knowledge, we selected 12 focused on science, technology, and medicine to publish as a special open-access issue of BJHS Themes: "Learning by the Book: Manuals and Handbooks in the History of Science."

Jennifer Rampling, Angela Creager (center), and the participants of the "Learning by the Book" conference with an alchemical manuscript, the Leonard Smethley roll, June 2018. The exhibit "Through a Glass Darkly: Alchemy and the Ripley Scrolls, 1400–1700" will open at Princeton University Library in spring 2022.

Manuals and Handbooks: A History

Manuals and handbooks have a long and cross-cultural history, stretching back to the ancient period. Practical knowledge need not be written down, as it was usually passed from master to apprentice, thus recorded instructions reflect certain cultural conditions of literacy, mobility, and circulation of textual media. Etymologically, manuals and handbooks should mean the same thing—they are books "on hand," or held in the hand, for instruction, reference, even as a place to store additional handwritten notes. The differentiation between manual and handbook has never been clear-cut, and, to make things worse, French only knows the manuel, while German relies on the Handbuch. Yet, there is evidence that the spectrum of literature designated especially by the Germanic term changed significantly in the modern period.

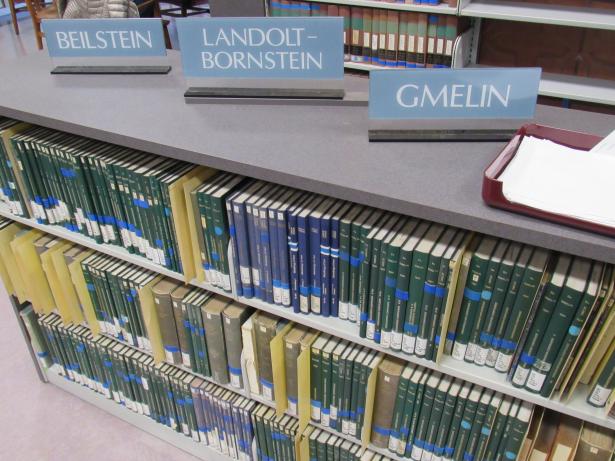

Unhandy handbooks: reference section of the Chemistry and Chemical Engineering Library, University of California at Berkeley, spring 2020. Photograph: Mathias Grote.

Over the nineteenth century scientific and technological handbooks developed a tendency to become "unhandy" in size and entire book series began to appear under this title. This transformation was certainly enabled by changes in the history of publication, such as the introduction of the steam-powered printing press and the mechanized production of cheap paper. Alongside these technological changes, the formation of scientific disciplines entailed other forms of writing, storing, and circulating knowledge in pedagogy and in technical practice, further encouraging the expansion of instructional or reference literature. Many such handbooks were not restricted (if they ever had been) to merely conveying instructional information. Rather, they offered the précis of a discipline or field, or ordered inventories of their objects, such as of chemical substances or biological species. These comprehensive handbooks emerged in response to other changes in the production, circulation, and differentiation of scientific literatures, not least the emergence of the modern scientific journal as a periodical form of print.

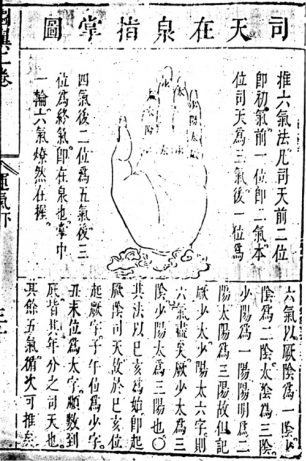

Diagram of 司天 (Sī Tiān, govern-Heaven) and 在泉 (Zaì Quán, in-the-source) hand mnemonic, in Zhang Jiebin 張介賓 (1563–1640), Classified [Inner] Canon, with Illustrations and Commentary (Leijing tu yi 類經圖翼), 1624 first edition, Rare Books Collection, National Central Library, Taiwan. The twelve positions divide annual seasonal change into six steps; the surrounding text explains where to find each step on the fingers, concluding: "With one revolution in the palm, understanding the six qi is within one's grasp."

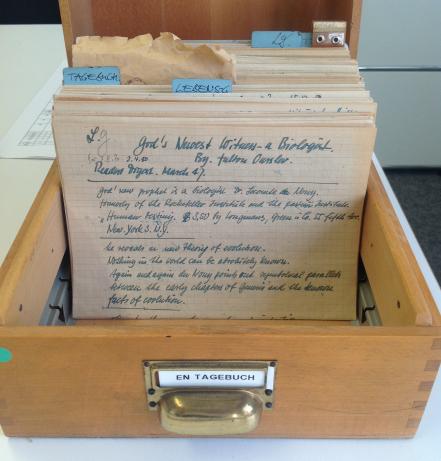

Ernst Neufert's diary in its original state as card index. Archiv der Moderne, Bauhaus-Universität Weimar. Photograph: Anna-Maria Meister.

The Lives and Afterlives of Manuals and Handbooks

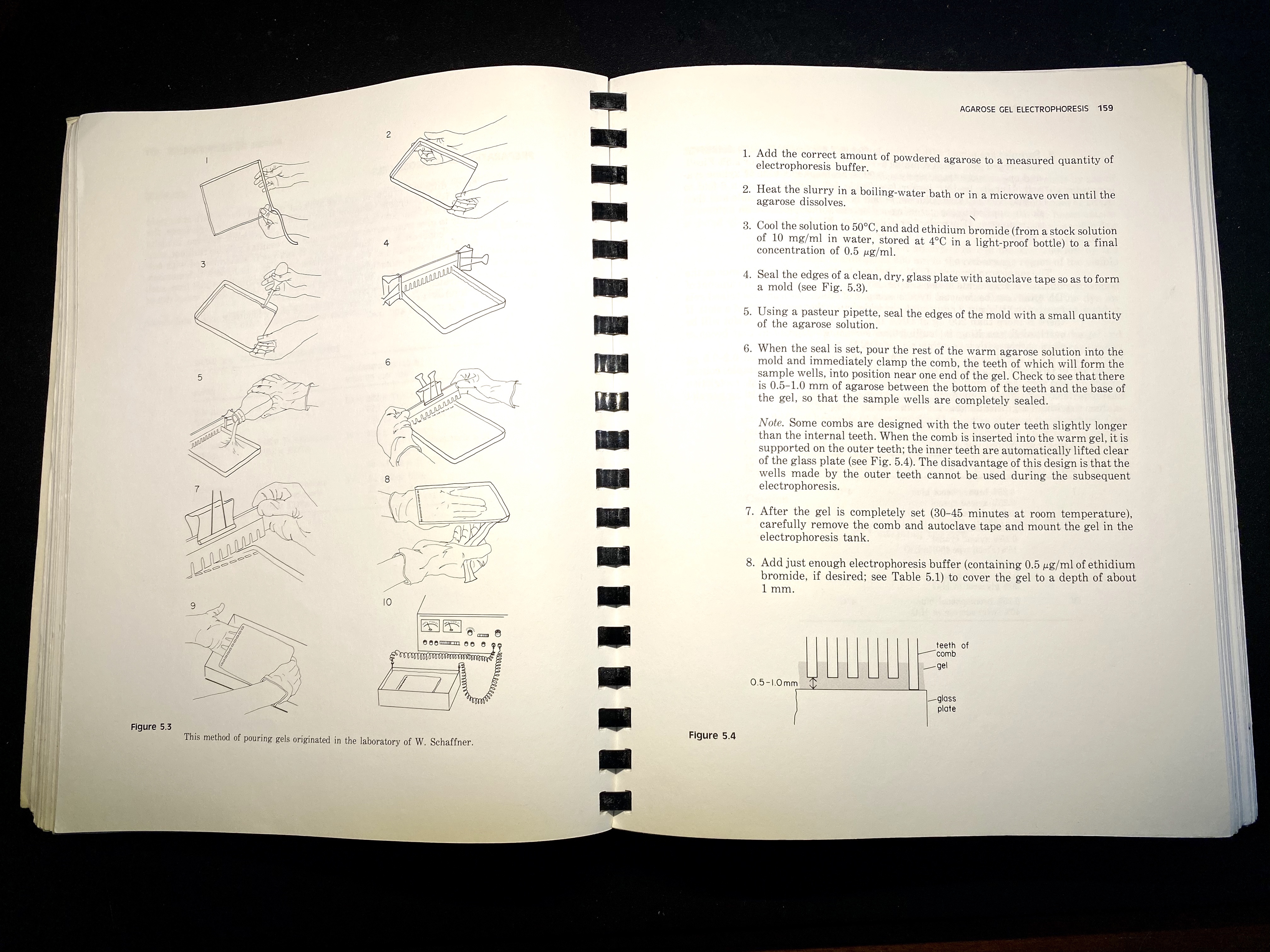

Our contributors brought vivid detail and specificity to this genre’s history , while also illuminating other themes concerning how knowledge is preserved, transmitted, and taught. Our collection opens with investigation of the conceptual and material work involved in making manuals and handbooks, e.g., by compilation, re-writing, and excerpting (see Matteo Martelli on late antique alchemy, Marta Hanson on Chinese medical instructions, Federico Marcon on natural history in early modern Japan, Mathias Grote on encyclopedic handbooks of the modern life and chemical sciences, and Anna-Maria Meister on architecture in twentieth-century Germany). Secondly, our authors shine light on the multiple ways in which these texts were read and used: from books as artifacts in science of early modern England (Boris Jardine) to instructions for cutting-edge technologies such as recombinant DNA (Angela Creager) and computing (Stephanie Dick) in the United States. Our volume closes with a group of essays highlighting the rich afterlives of manuals and handbooks in various contexts from medieval Chinese mathematics (Karine Chemla), to early modern alchemy (Jennifer Rampling) and medicine (Elaine Leong), to twentieth-century Mendelian genetics (Staffan Müller-Wille and Giuditta Parolini).

Instructions and diagram for a molecular biology routine from T. Maniatis, E. Fritsch and J. Sambrook, Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual (Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 1982).

Guiding Thoughts in the Age of YouTube

The collection invites readers to ask new questions about settled knowledge. How are traditional practices and protocols preserved or discarded, and how are the naming and ordering of objects or processes renegotiated in an age when nomenclatures, taxonomies, or bibliographies become ever more rapidly outdated? In the twenty-first century, the once-ubiquitous owner’s manual has been superseded by instructional videos on YouTube. Is this a return to past practice, or the reinvention of the manual in a new guise? We have more information at hand than ever before, and yet often struggle to find certified knowledge. As we continue to see how the internet has and has not altered learning, we hope this collective history may prove a handy guide.

Digital book launch of the "Learning by the Book" collective, January 2021.