"LoGaRT: History 4.0"—Big Data and Digital Humanities with Shih-Pei Chen and Joe Dennis

Digitization has changed our present lives in many unexpected ways—also for historical research. So what happens if we look at the past through a digital lens?

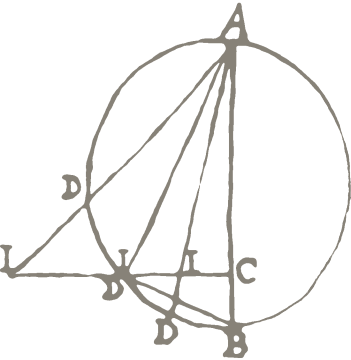

Scholars Shih-Pei Chen and Joseph Dennis use LoGaRT, a set of online digital tools for investigating a historical resource called Chinese Local Gazetteers. In doing so they work at an intersection between history and Big Data, and where digitization is transforming an entire academic field.

In this third episode of the Science Social podcast, Shih-Pei and Joseph chat about open access, the differences between doing research pre- and post-digitization, and why it's sometimes smarter not to wait for that copy of a hard-to-get book. And yes, we'll also explain why Local Gazetteers are the most amazing written works you've probably never heard of!

Transcript

-

"LoGaRT: History 4.0"

Joseph Dennis: You find one thing and then you try to generalize from it. But tools like LoGaRT allow you to find and aggregate things that show patterns that you just wouldn't spototherwise.

Shih-Pei Chen: That also shows the possibility of what computers can now help us with.

Stephanie Hood: Science Social, a podcast series about how science, history and society connect with and add to the big questions that we all have today. This show is created by the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science. My name is Stephanie Hood and in each episode, I'm joined by guests from our institute to talk about their research, their big questions and some of the weird and wonderful experiences they've had along the way.

Stephanie Hood: I'm here today with Shi-Pei Chen and Jo(seph) Dennis, who are part of our Department III “Artifacts, Action and Knowledge”. We're here to talk about LoGaRT, the Local Gazetteers Research Tools. So, Shi-Pei is our digital content curator and Joe Dennis is a visiting scholar. So the first thing I wanted to actually ask you was why a local gazetteer is really cool.

Joseph Dennis: Why are local gazetteers really cool? Well, because they're the best kind of book there is. Local gazetteers contain all kinds of information that you can't find in other places.

Shih-Pei Chen: For example, if you want to find a list of mountains and rivers, you want to find the local products, what kind of products are provided or are produced in this region, then you can find them from all the Local Gazetteers that exist today.

Joseph Dennis: They're really rich sources for digging into all kinds of different questions. So there's a very large number of them and they come from all different parts of China. Another thing that's really special about them is that they're tied to a particular place and they're issued in multiple editions over the late Imperial Age, the Republican period, and into modern the People's Republic of China. So, this allows you to see how things have changed over time. You can get different snapshots from different periods of the same place.

Stephanie Hood: Jo(seph), your previous books dealt with local gazetteers and their political contexts. Can you tell me just a bit more about local gazetteers and those contexts?

Joseph Dennis: So, on the politics, one of the things I did when I was starting the book on local gazetteers was look at one particular gazetteer and I looked at all the compilers and how their family connections, how they're connected to each other through family relations. When you do that, then you can see, oh, this is a very tight family network that produced this local gazetteer. Some people would use gazetteers to put forward their own views on local history that might be beneficial to their particular family or political faction. So, even though gazetters seem very similar that something you need to keep in mind when you're trying to construct a large database of data extracted from Gazetteers.Stephanie Hood: Shih-Pei, you recently co-published an article about disasters and local knowledge in local gazetteers. One of the results was that there may have been some political manipulation going on in those chronicles. Is that right?

Shih-Pei Chen: Yeah. The local gazetteers seem like a very objective genre, like a place for storing records or storing just facts. What Dagmar Schäfer and I have been working on is about collecting disasters that related to mulberry trees. But after we collected disaster data from 4,000 local gazetteers, what we found is that those data actually concentrate a lot on a very specific dynasty and around also the northern China, rather than throughout all the different time periods and throughout all the territories of historical China. So that was a bit striking for us. It's only possible that after you are able to collect a lot of records from many, many different kinds of local gazetteers, that we start to realize that those data are actually not totally objective. So, through the LoGaR-tool, this probably is the first time that we are able, or scholars are able to collect large amount of data from this genre.

Stephanie Hood: So, this is a really fundamental question. I wanted to ask you both about LoGaRT as an example of a digital tool and digitalization and... put really simply, what is LoGaRT?

Shih-Pei Chen: There are at least 9,000 titles of historical local gazetteers that are still around. Among those titles, at least half of them is already digitized, not only as scanned images but also as searchable full text. And you can imagine that with the searching technology that we have right now, for example, you can go to Google and search like billions or trillions of web pages. And you can imagine that with that kind of technology, what we can do right now with the digitized local gazetteers. And what LoGaRT does is that we can search through the contents. If you're interested in a temple or you're interested in a person or a historical book, you can simply type in a digital database for local gazetteers and you can find where and when those people, temples or book titles were mentioned and in what context. So that gives really a very high level or large-scale view of how we understand certain things in historical China.

Stephanie Hood: Why did you decide to create LoGaRT in the first place?

Shih-Pei Chen: So, there are already some other digital databases that are dedicated for local gazetteers. But what they do is normally that they provide very good reading environment for individual local gazetteers. But one thing that they haven't been providing is a large-scale analytical tool that helps the researchers to understand the overview of their search results. For example, is there any pattern, any temporal or geographical pattern of certain keywords that appear in the local gazetteers? So, it is the lack of those analytical large-scale tools that pushes us to develop LoGaRT.

Stephanie Hood: Maybe we should also give out a shout to your IT developer that you're talking about, Sean, right?

Shih-Pei Chen: We are actually talking about Calvin. With him, there is no problem.

Stephanie Hood: Just on record. Make sure that's definitely recorded.

Shih-Pei Chen: Yeah, he’s great. Yeah.

Stephanie Hood: Is there anyone else actually that we should make sure we mention?

Shih-Pei Chen: We should also mention Sean. So, Sean has been helping us to manage the whole project.

Stephanie Hood: Okay, special shoutout for Sean and Calvin. This one's for you. I actually also have had a little play around with it myself and just like the scale of what you can find out I find kind of phenomenal. Also, just really funny to me knowing that you were working on this for such a long time and I kind of vaguely knew what it was and had no idea of the scale or extent of it.

So, Jo(seph), how have you approached your projects prior to LoGaRT and how might LoGaRT have helped you on your previous project or how are you using LoGaRT for your projects right now?

Joseph Dennis: So, in my previous book on gazetteers, this was done before the digital age. I collected lots and lots of material from different libraries and went manually through lots of gazetteers to see how they were compiled.

So, then I got really excited by Shi-Pei's software because it made it possible to do a whole range of projects. In fact, I could have written this book a lot faster if I had LoGaRT 15 years ago, because it helps you find little bits of information that you really can't find if you're just flipping through. With a big data set like this, you see patterns that you wouldn't see otherwise, and you can also judge whether or not something's typical or atypical. It makes possible new kinds of questions and new kinds of research. One of the things that's really powerful about it is the section searching. So, if you're just looking, if you just Google something, you might get a million hits. But LoGaRT allows you to search in the right places in the local gazette because the sections have been marked up already. So, when I say marking up, LoGaRT allows you to tag text that you find. So, you bring up a section and then eliminate the stuff that you don't want and then mark any other kind of information that's relevant can be put into a category and then export it as a data file. So, you put it in an Excel spreadsheet or a CSV file, and you build up a data set that can then be used in much more sophisticated analytical tools.

Shih-Pei Chen: Basically, you turn the text that was originally only meaningless strings for computers, you turn that into a meaningful structure for computers, so that computers can later on analyze that for you. So that is the tagging interface Jo(seph) is talking about.

Joseph Dennis: Yeah, and then you can map things too with LoGaRT. For example, I was interested in a book that a bunch of scholars have written about and with LoGaRT I was able to show that this book circulated in about a third of Chinese school libraries. Having this massive data on circulation of particular books gives you a better sense of the influence of a book.

Stephanie Hood: That probably leads us quite well to the next section that I wanted to discuss about digitization and research more generally. So, I wanted to ask you why is developing digital tools like LoGaRT so helpful or so important for the history of science and the humanities in a broader sense do you think?

Joseph Dennis: I think for historians and historians of science, one of the big issues is if you're trying to find out new things from the same set of sources that have been in existence and accessible to people for a long time, either you find new sources or you find new ways to deal with the sources you have. And LoGaRT is something that allows you to look at things in new ways. I think that one of the great things about a lot of digital-based research is that it gives you new findings that were unexpected that will take you in new directions and lead you to other people.

Stephanie Hood: Either of you, what do you think of when you think of digitization and open science access to research data? Because I know that at the moment, I mean, you're trying to make these resources available on a much bigger scale.

Shih-Pei Chen: So, in the past decade, I think there are also some historians that have devoted time to collect information and compile databases for not only for themselves, but also for the others to use. But such work or such effort has not been properly attributed in a way that can help their academic career.

Joseph Dennis: I think historians get credit for writing articles and books that make a historical argument. This is a little bit different. The creation and curation of a data set is not something that has been valued. I'm thinking of this guy Robert Hardwell who did all this work to create a lot of the data that's under the China Biographical Database. It's tremendously useful, people use it all the time maybe retroactively everybody says, oh, atta boy! That kind of thing. But the person who did the initial work to make this possible, I don't think he got a lot of credit for it.

Shih-Pei Chen: This is what we have been seeing that in the past decade when some young scholars, they devoted so much time into collecting information for the others to use, but in terms of evaluation when they want to get a permanent job, because they have put so much time in doing these works and they probably don't have their first book out, for example. Then they lost the chance.

Joseph Dennis: The difference in the sciences. You have biologists who study basic processes, other ones who make drugs. And they're connected, the ones who make the drugs have to have an understanding of the basic biology. So, somebody had to do that underlying foundational work and I think a lot in academic history there's a desire to go straight to the kind of the drug production to an end theoretical interpretive result without having an adequate foundation of sources built. So, part of this is we're trying to figure out how do you get people to value these kinds of projects.

Shih-Pei Chen: So, this is a problem that we also want to address in this digital age. So one thing that we are doing right now, like Jo(seph) is doing right now, is that he's using LoGaRT to collect a lot of book lists from local school libraries. And then after that, what he wants to do is also to put these data on the web so that the others can use them. In order to do that, we start to think about whether there is a, first of all, a better crediting system that can give Jo(seph) credits. And the other is that whether there can be another kind of user interface that can help the other historians to query this dataset. Programming is not, normally not part of the training for humanists or historians. So, what we want to do is also to develop a user interface that can help the other scholars to dig into a dataset that either that is curated by Jo(seph) or curated by other historians.

Stephanie Hood: I feel like everything, I would say, somehow ends up coming back to the COVID-19 pandemic. You can make connections everywhere. But one of the problems I know a lot of historians are having at the moment is just being able to access the archives that they would usually access. They can't travel to other parts of the world. They can't necessarily, even if their archives are in the city or the place that they live in, they can't necessarily access them. So how would you have accessed these materials before LoGaRT existed? Has this changed your ability to do your research?

Joseph Dennis: Yeah, I have a lot to say about this. So, there's some connected issues here about just access for people. And there's different kinds of problems. One is your home university doesn't have the things that there's travel bans because of COVID. You just don't have research money. A foreign government is preventing you from looking at things. I mean, there's a whole host of things that make things difficult. And this is actually becoming a much more important thing for scholars of China because in the last years, it's become difficult to get access to archives in China and libraries. Looking at rare books has become more difficult. So, this kind of digital set allows you to do that much more efficiently from your own home computer.

Shih-Pei Chen: Yeah, and what I can add to that is that so our content in LoGaRT is mostly commercial text. So basically, only our affiliates from MPI can really access them. And that is of course not ideal because now we have this very powerful tool and we definitely want it to be used by more scholars. So, what we did is that we contacted the Harvard-Yenching Library and they have digitized their contents for open access usage. In their rare Chinese book collection, they also have some local gazetteers. So, we applied for funding and we basically digitized them by sending all the images over to a typing company and we specify how we want to type them. For example, if they encounter images, then what should they type? One thing very nice is that we also ask them to type in whatever text is in an image. So, for example, when they are typing a map, if there are already some place names in the map, they would also type them. And that actually allows the image search function that is very, very useful because in many cases that some place is not really mentioned in the text, but you canstill find them in the map.

Stephanie Hood: A lot of the information that we communicate is digital today and in that way it's somehow disembodied, there's no material object attached to it. What do you think that this means for the work of historical scholarship?

Joseph Dennis: It really depends on what you're trying to do. So, this large-scale aggregation that becomes really separated from the actual material object is a different kind of research. Now some people I'm sure are doing research that is completely disembodied. They don't go back to the original. For example, in my own project, I have like 30,000 different books in this dataset and there's multiple data points about each book. It informed me about my research topic, but then I also had to track down all kinds of other things and do the regular kind of historical research of following up. So, for me in particular, the disembodied data leads me to things that I have to clarify with other kinds of methods.

I think these are just things you have to keep in mind as you're doing your work. What is the importance of the material object in what you're doing? So, for example, with Gazetteers, if you wanted to do a study of the paper or the production, maybe you really need to go to the libraries and look at the particular objects and find a way to get access to them, but so many things now it's harder to get access to. If you have books from the 1400s or 1500s, a lot of libraries don't really want you flipping through them like they did even 10 or 15 years ago. So, I think the digitization has also enabled a different kind of sort of protectionism by

libraries to treat the underlying objects as, more like museum objects and not just text that scholars, that historians will look at and then use to talk about the period.Can I just give one little anecdote about the difference between different formats? Some years ago I really needed to look at one book for something I was working on. There was a copy in the Zhejiang Provincial Library and I was giving a paper at Zhejiang University. So I went to the library. I had an introduction from somebody who used to work at the library and they said, well, you know, you can't see that book because it's too hot and if there's a certain temperature and humidity they wouldn't bring out the rare books. I had a hotel for a week, so I went back the next day. Same thing. Of course, every day, because it was in the summer. And I said, well, when do you think I'd be able to see it? They said, maybe October. And so then I left and I had wasted this week and I went to Shanghai to get my plane back to the United States. And I went into the something called the classics bookstore and there's a company that was reprinting old rare books and they had printed an actual better copy of it from a different library and so I just paid like a hundred fifty dollars for this string bound beautiful book, took it home and had it. And now this book is in one of the databases that you can access here. So basically, that whole week was kind of frittered away for something that for my particular kind of research, I just needed the text. I didn't need to know what the paper was or the printing or the anything like that.

Stephanie Hood: There are worse places to be than Hangzhou for a week, I guess. Well, that is awesome. What were the chances? I mean, also, if you'd walked into any other place.

Joseph Dennis: I was so surprised.

Stephanie Hood: I assume you still have the book now? It's got a special place on your bookshelf?

Joseph Dennis: It's got a special place right on my shelf.

Stephanie Hood: Okay, I love that story. That's actually a really nice place to tie up, I think. Could you just tell me how our listeners can actually access LoGaRT?

Shih-Pei Chen: We have two sets of local gazetteers that are connected in LoGaRT right now. So, the first is a commercial set for that you need to be affiliated with the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in order to use them. So, we now have an open access digital local gazetteers collection from Harvard-Yenching Library. So that one is totally free and open access. What you need to do is only to visit our website and then you can register for an account, then you can immediately use it. And that one also comes with very high-quality image scans. Yeah, so the other possibility is that LoGaRT itself is also a software package, meaning that if some library or some university has their own digital collection of local gazetteers, then they can also link that with LoGaRT.

Stephanie Hood: So I think I can finish off by saying thank you so much Jo and Shih-Pei for joining me and for telling me all about LoGaRT. I'm really excited to see what comes out of this, all the fantastic opportunities and yeah, to be continued. Thank you.

Joseph Dennis: Thank you, Stephanie.

Stephanie Hood: This is it for today. If you like what you just heard, we love your support. Click the subscribe button, recommend this to your friends and colleagues, or give us a thumbs up in your favorite podcast app. You can find us on iTunes, Spotify and anywhere else you can listen to podcasts.

Science Social is produced by the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science. Music by Poddington Bear, and I'm the host, Stephanie Hood.

Make sure to follow us on Twitter at @MPIWG. And most of all, thanks for listening.

Copyrights

Produced by the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science; Theme song by Podington Bear, CC NY-NC 3.0