"The Mask—Arrayed": Unmasking the mask with Carolin Roeder and Marianna Szczygielska

It seems straightforward: we wear a mask because it protects us from pollution, from a contagious virus. Yet the Covid-19 pandemic has taught us that this seemingly simple object can also become a powerful symbol—one that can divide or unite us, silence or empower us. So how is it that this small piece of fabric can have political meaning? What role does it play in different cultures around the globe? And what can a mask reveal to us about social inequalities?

It seems straightforward: we wear a mask because it protects us from pollution, from a contagious virus. Yet the Covid-19 pandemic has taught us that this seemingly simple object can also become a powerful symbol—one that can divide or unite us, silence or empower us. So how is it that this small piece of fabric can have political meaning? What role does it play in different cultures around the globe? And what can a mask reveal to us about social inequalities?

In this second episode of "Science Social," scholars Carolin Roeder and Marianna Szczygielska unveil layer by layer the hidden stories of perhaps the most iconic object of the coronavirus pandemic: the face mask.

Transcript

-

"The Mask—Arrayed"

Marianna Szczygielska: Masks, because they're such everyday objects of use, they also become a canvas in which people express their political ideas and proclivities.

Carolin Roeder: If you believe that there is always a material base to culture and society, then yes, of course. The way how people deal and think about the material objects that surround them, of course, highlights social issues.

Stephanie Hood: Science Social, a podcast series about how science, history and society connect with and add to the big questions that we all have today. This show is created by the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science. My name's Stephanie Hood and in each episode I'm joined by guests from our institute to talk about their research, their big questions and some of the weird and wonderful experiences they've had along the way.

Stephanie Hood: I'm here today with Caroline Roeder and Marianna Szczygielska to talk about “The Mask—Arrayed”, a project that they've started during the COVID-19 crisis looking at the probably most iconic artefact of the pandemic, the face mask. So, the project looks at the material, technological and cultural aspects of the face mask through essays and through artwork.

So, yeah, I wanted to know what your favorite masks were, either as part of the project or out and about. Marianna?

Marianna Szczygielska: I can start with that with mine. So, I think the most fascinating mask I've seen is these masks that were designed for horses during World War I. So, there are these kind of gas masks for a horse head, horse snout for protecting from military gases. And I think it's a very weird object. And you can see it sometimes in some military museums.

Stephanie Hood: I was totally not expecting that. I was thinking like panda face masks or something. That would be mine. Caroline, you look like a fan of a panda face mask.

Carolin Roeder: I can offer the panda face mask. Well, you mean like face mask with the panda on? Not with a panda, but with Donald Duck. So, I think that the mask is in some ways fascinating because it brought really sort of to material life this idea of transforming material as the first mask my mom made for me. And she made it from her children's bed linen. So the ones that she actually had as a baby from a Donald Duck and Mickey Mouse print. And thinking that this material used to be her linen and that she kept it, and she's not someone who keeps a lot of things, but that piece of cloth was still there and then she made face masks from it to protect her adult daughter in this crisis was just something that I thought was really interesting how also quite often textiles are inherited.

Now I have the Donald Duck face mask. I'm a big Donald Duck fan as well. So, I wore it proudly and I was always waiting that people would say, oh my God, wow, I love your Donald Duck mask. And I think I was one of the first ones with a comic mask, but nobody ever said anything. That was a bit disappointing.

Stephanie Hood: If I had seen it, I would have complimented you on your Donald Duck mask. Thank you. Just swing by my office sometime with it on and I'll give you a thumbs up. So, what's the story behind the project name Masquerade? What meaning does it have for you?

Carolin Roeder: Well, initially the project was called “Masks of Desire”. There was a time when masks of all sorts were still short in supply, and I said, oh, this is all what we desire now, our masks. And once the project evolved and time went on, I realized it's actually a bit more complicated. Not everyone necessarily desires the mask. It's also an object of fear. Our team member Jadie suggested this title, “The Mask—Arrayed”, because it now reflects that we have an array of stories and an array of different perspectives about the mask as an object and that there is actually something behind, hiding behind the material that we want to unmask.

Marianna Szczygielska: And I think another important part of it was that we had… early on we had artists on board. And they were working on something that could be more closer to a masquerade because they were producing items, material masks, and we have of course on the webpage visualizations of those objects, but it was really important for us to have—in a masquerade—to have an actual mask produced for us and that happened.

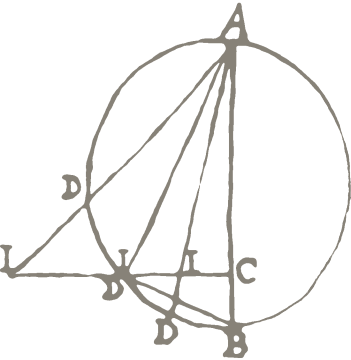

Stephanie Hood: So, on the landing page of “The Mask—Arrayed” you have a collage of various people or characters wearing masks. Where did this come from? Where did the idea come from? Can you tell me more?

Marianna Szczygielska: This is a direct contribution from one of our collaborators, Regina Maria Müller, who's an artist based in Berlin. In this collage you can see images from different time periods, from different cultures, and etc., kind of being together in this brie collage manner.

Carolin Roeder: Collages of course also consist of layers and many of them are particularly the respirators, consist of different layers of fabric. And so, the collage also represents that layering of both meanings and material.

Marianna Szczygielska: We could say that this is a visual representation of our take on the mask and the project. Because from the very beginning we wanted to show the many layers of the mask opening, but at the same time I think it shows how the collaboration was also a multi-layered process for us.

Stephanie Hood: How did that work actually collaborating during COVID-19? Because the pandemic's changed working practices for many of us around the world, including academics.

Carolin Roeder: Right, so we pretty quickly decided that we're going to look at different kinds of software that will enable us different kinds of work to do collaboratively online. So, we settled on Slack that would enable us communication and then Notion where we shared our ideas. I actually think that it worked particularly well because meeting online is... If you're available at home, the barrier is very low in some ways. And that also helped us to include scholars who were based, for example, in Canada, without making them feel less a member of a team because they weren't physically around.

Marianna Szczygielska: I think there were also those meetings were about the project, but everybody was also reporting what's going on, you know, where they're based. So, we were asking colleagues in Stockholm, how is it there? Because at that time in Berlin, we were under complete strict lockdown, whereas in Stockholm, you could go to cafes and somebody was actually visiting us from a cafe and we were all like, oh, wow, you can still do that there. And that was definitely an interesting experience.

Carolin Roeder: I definitely also felt that I missed just walking into someone's office and saying, hey, could you help out with this? But it was also, I think, very important for us in terms of mental health to have to see each other and actually work on something that was related to the crisis where we felt that we can contribute something and there is actually something that our discipline can answer or observe. So, it was also practice for all of us to see how can we, with the questions we usually deal, maybe in the context of other projects, how can we deliver some answers or maybe just some good questions or some just good ideas. I guess we were delivering more ideas and ways to think about things and then in fact answers.

Stephanie Hood: Your department, Department III, is called “Artifacts, Actions, and Knowledge” and focuses specifically on materiality. But what does that mean on a bigger scale in history and sociology of science, but also when you're looking at the mask? What does that mean about the mask? What do you mean when you talk about the materiality of the mask?

Marianna Szczygielska: Yeah, so we come from a perspective where knowledge making doesn't happen in just like some void space or abstract reality, but like all aspects of knowledge making have their material dimensions. Maybe traditionally history is perceived to be dealing with texts and archives and narratives, but also there's this huge material turn in humanities and social sciences and there are certain aspects of the historical discipline, especially history of science, that pays more attention to the material cultures and the materiality of objects that can tell us something about the world.

Stephanie Hood: What kind of example can you give us from everyday life?

Carolin Roeder: I'm thinking of Christmas trees, I don't know why. A Christmas tree is really, you know, if you think the most simple term that celebrations are a part of your culture, and you say, well, I have to have a Christmas tree, maybe because I don't believe in Santa Claus or… I’m not religious, but the Christmas tree is just part of my culture. I think that's an item where even if you feel just remotely related to a certain kind of tradition. There is an item that needs to be there. It needs to be treated in a certain way. It has a specific spot. Then it has a very universal appeal of the tree as such across human cultures. And it has a material life and that it needs to be grown organically and cut and then being disposed off. I actually saw the last Christmas tree in Berlin a few weeks ago just in a bush, so there is an environmental history to the tree. And yeah, you know, you could go on and on about the tree.

Stephanie Hood: Also, somehow about the fact that we're talking about Christmas in like 30 degree heat.

Marianna Szczygielska: And I guess if I can add something coming from that kind of perspective, every object literally could be turned into a heuristic tool to understand the reality and culture around it. So, for us deciding that a mask will be such an object also because it became a very significant object at the time. What it could tell us about the processes, the changes and of course as every object that is material and concrete it has its own history. So, we were interested in delving into what those histories are, how people use it differently in different places and how it's distributed differently and also really what it's made of.

Stephanie Hood: Something that your “Mask—Arrayed” project also teaches us is that the mask really has a history. This is probably a mean question but can you give me a short history of the mask? Just a run through.

Carolin Roeder: I would say if we talk about the mask, the mask is of course one of the oldest, or like a staple item in human cultures. So, there are certain functions that some masks have in different contexts and lots of them are objects that aid transformation in some way from life to death or transforming to someone else or something else on stage for example. What we're particularly interested in are masks with protective function. They're particle respirators, lots of them. So that's also why in the beginning I was interested in basically three materials meet each other. It's the body and then it's the mask as a barrier and then there's something else that should not enter your body.

Marianna Szczygielska: There's so many different masks that we're talking about, because there's a simple surgical face mask, but there's also N95 respirator, which is a bit of a different protective item. And there's visors and different kinds of masks, so they all have their separate histories. But also, what Caroline was saying about historical circumstances that make wearing masks a pattern in different societies visible.

Carolin Roeder: A common trope that has been popular since the start of the crisis is this idea that Asian cultures already wear a mask and hence, they might have been better productive or they have these higher levels of hygiene and that also of course you know—what is Asia? Every Asian country as such and culture also has different histories of how masks are used. You definitely cannot put Japanese and Chinese and South Koreans into just one pot and say all Asians wear masks. South Koreans for example started wearing masks to protect themselves against pollution. So environmental pollution is actually one of the main reasons which is also actually related to the origins of the respirator because initially they were really there to protect you from dusk and their histories are in the history of mining and workers protection. And there's of course also the much shorter history of SARS where those masks come up. And so, this is really contemporary history and from country to country different and that's also our contribution to show these differences.

Stephanie Hood: We've seen on your “Mask—Arrayed” project that masks have become connected to other social issues during the COVID-19 crisis, could you expand and tell me a bit more about a couple of cases that you've seen?

Carolin Roeder: We do have a pre-corona project featured on our project website in form of an interview with a Vietnamese artist who created also a protest project using face mask and printing fish on them, fish that died during an environmental crisis in Vietnam. There the face mask also stood for “we won't be silenced”. And this idea that a face mask can silence you but also empowers you and in some really interesting weird ways is coupled by all sorts of political and social groups. Another interesting case—I think the CS case, where the mask became so politicized—there are so many cases where people wearing masks were asked, oh, are you Democrats? It becomes a political party statement, all of a sudden, this object of protection.

And also related to, we saw that in Germany too, to violence and anger. So, it is an object that in some ways the power and truth-seeking forces of all sides try to co-opt and really imprint their own meaning to it, to a very physical object. And I think this is where the power of material culture also really shows.

Marianna Szczygielska: The example that comes to my mind immediately is actually something that's happening right now in Poland, where there's a big wave of homophobic laws and homophobia at the moment. And the rainbow has become a huge symbol of resistance and of fighting for tolerance and freedom. And people who wear masks with rainbows are just communicating something very important to the others. They're also kind of brave because you can get into trouble for that. But for example, when the president was sworn in the parliament, several MPs from the left party decided to protest. Some of them were wearing rainbow masks and others were wearing clothes that formed a rainbow when they were sitting in their seats. So, this kind of simple colors on your mask can communicate so much in very specific social situations and contexts.

Stephanie Hood: Gender actually is one of the other many themes that the mask touches. So, in your article you ask would a respirator modeled on a female body look or function differently? Can you observe differences in how masks look or work differently for men and women? So, for example, in fashion or medicine?

Marianna Szczygielska: This was a speculative question of course, because they seem to be just the same. So, the standard masks that are used by professionals, by medical professionals, they actually look really the same. There's of course different sizing in masks, but the look of it is almost uniform. But then we do put masks on different bodies and differently gendered bodies. And there has been done some research on mask wearing of the N95 respirator by pregnant women and whether making it more comfortable for women who are pregnant would kind of lead to making a more comfortable mask for everyone. So that could be something that could benefit everybody actually if we took into consideration certain gender differences and how masks are being fit because with respirators especially the most important thing is a proper fit of the of the mask around the face.

But that kind of leads us to also thinking about whether gender at all matters with such a simple object that says something that attaches to your face and maybe that we don't need to think about gender at all, and maybe masks should be just adjusted to different bodies, like differently shaped bodies and etc. That for sure can be more visible when we get out of the realm of the professional masks and to the masks that are DIY or designed by fashion designers.

But also, for example, it makes me think of the masks that have a clear window where your mouth is. And this way they allow you to communicate emotions still while wearing a mask. But at the same time they are very important for people with hearing disparities. They can actually look at the mouth and read your lips if people need to do that. So those are important ways that masks are modified along lines of differences and how our bodies are different than our lives.

Stephanie Hood: It kind of makes me want to expand a bit more on the ability/disability. I also find this when I have really bad eyesight, I'm like minus eight, and when I don't wear my glasses, I really struggle to understand what people are saying. But that's weird, right? Because I still listen to podcasts, I still listen to audiobooks. I don't have a problem understanding those. But I think, if anything, then that just highlights something that we see in... well I also hear a lot about—since the COVID-19 pandemic started—the new inequalities that have come about, but also the ways that existing inequalities have been strengthened by aspects of COVID-19, whether it's work, culture, or people with children, or people with certain disabilities.

Carolin Roeder: Actually, today I worked with someone and she works with transplants. And she cannot… she needs to see, she doesn't read from the lips, but she still needs to see what is going on in your face.

Marianna Szczygielska: You mean like expressing emotions?

Carolin Roeder: She said she needs her transplants in combination. She needs to see you and hear you to actually be able to process that.

Stephanie Hood: Are there any other examples that you found in the “Mask—Arrayed” project of how these kinds of structural inequalities have been deepened by COVID-19. Specific examples that you've seen?

Carolin Roeder: One thing that we still would like to explore, and would invite any author writing about that, is about mask and race and depending on your cultural context. There have been other outlets that have been written about the problems of black Americans being able to wear a mask because when you do cover up your face and you walk into a store the chance that you're going to be shot or harassed or the police being called to you is pretty high. And that sends the legitimacy or the ability to cover up and not show your face is a privilege that not everyone has. There is definitely the community programs to help people to get access to masks if they can't afford them. So, for example in Berlin, the “Bezirksverwaltungen”, were giving out masks for people with low income. I think they did not ask them to prove low income. Because even the community mask is not necessarily a cheap item. They started off with, you know, 10 euros when you go to a tailor and buy a mask. You need several because you have to change them often, you have to wash them frequently.

Prices are going down, but even a surgical mask in the beginning if you bought like a single one at a drugstore and those are single-use items were four euros and that is actual money. So, there is a financial aspect to the crisis beyond just losing your job but actually being able to afford protective gear.

Stephanie Hood: What in your opinion can we learn from that? About the mask, about the crisis and about ourselves?

Marianna Szczygielska: Definitely that a mask is such an object that became super close to our body. It became almost like a personal and intimate object that we carry along and we have to make peace with and use and learn how to use it.

Carolin Roeder: I think that one contribution historians of science, I think in having these times is to communicate to people to keep their minds open about both the objects and the ways how they think knowledge is produced about these objects and what these objects do with us and for us and what we do with these objects. But understanding how complicated it sometimes is to reach a level of certainty about objects and how we should live with them. I think caring that kind of knowledge would maybe allow people to also cut some slack. And that kind of tolerance and openness, I think that is hopefully something we can communicate with this project.

Stephanie Hood: So where do you see the next project going? What are your next steps do you think?

Marianna Szczygielska: You can check our website at www.themaskarrayed.net and we are still uploading new essays that are incoming and we are also open to proposals and suggestions. So, if anyone would like to feel like suggesting, pitching us an idea, please contact us. And that goes to scholars, but also artists and professionals.

Stephanie Hood: This is it for today. If you like what you just heard, we’d love your support. Hit the subscribe button, recommend this to your friends and colleagues, or give us a thumbs up on your favorite podcast app. You can find us on iTunes, Spotify, and anywhere else where you can listen to podcasts.

Science Social is produced by the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science. Music by Poddington Bear and I'm the host, Stephanie Hood.

Make sure to follow us on Twitter at @MPIWG and most of all, thanks for listening!

Copyrights

Produced by the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science; Theme song by Podington Bear, CC NY-NC 3.0