We add context to this here by considering the role of the natural sciences and, specifically, the communication between scientists in the work leading up to the discovery of ammonia synthesis.

My book, Making Ammonia, uses this momentous event to demonstrate how communication and interdisciplinary exchange create new scientific knowledge, enable problems to be solved, and drive breakthrough results towards industrial and social application. By focusing on the interaction between the physical chemists Fritz Haber and Walther Nernst on their way to the discovery of ammonia synthesis, I look to break down the complexity of scientific research. It doesn’t start or end with ammonia though. Understanding the social elements of a scientific breakthrough can help us navigate other major scientific and social challenges of today and into the future.

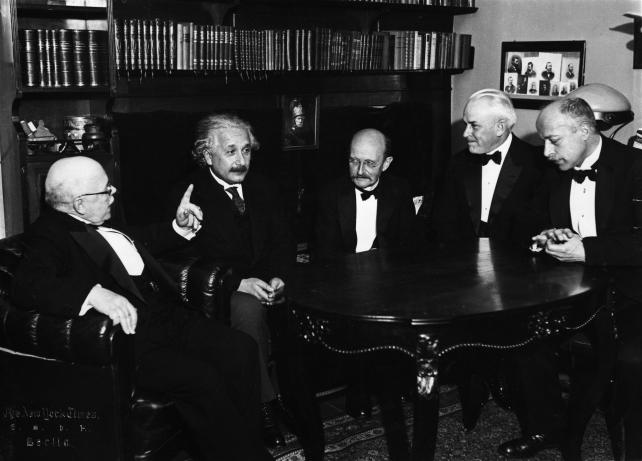

01: Scientists in discussion. From left: Walther Nernst, Albert Einstein, Max Planck, Robert Millikan, and Max von Laue in 1931. Source: Archive of the Max Planck Society, Berlin-Dahlem, III. Abt. Rep 57, NL Bosch; Akz 46/95, Picture Number III/2.

Understanding the Development of Modern Science: Complex Social Interconnections

Looking at the history of scientific and human factors that led to the breakthrough of ammonia synthesis can help us understand more generally how science develops. During the nineteenth century, agricultural science, energy science, and organic and physical chemistry had formed an exceedingly complex body of knowledge about nitrogen's chemical behavior and its impact on the human condition. In the first half of the nineteenth century, agricultural science determined the role of nitrogen and carbon in plant and animal growth by determining rudimentary forms of the nitrogen and carbon cycles in the biosphere and atmosphere. And chemists, having achieved some order out of the chaos of carbon-containing compounds, established organic chemistry as an independent discipline.

These advances led to the growth of the chemical industry in Britain and Germany in the second half of the century, where the prerequisites were met for new challenges such as ammonia synthesis. Finally, the combination of chemistry with energy science in the 1880s into the field of physical chemistry provided unprecedented control of chemical reactions such as the Sabatier process, which is still used today to make methanol out of carbon dioxide and hydrogen. By the beginning of the twentieth century, the stage was set for the discovery of ammonia synthesis. This story of a successful technological transition shows us that breakthroughs are not only scientific and technical, but also of a social nature.

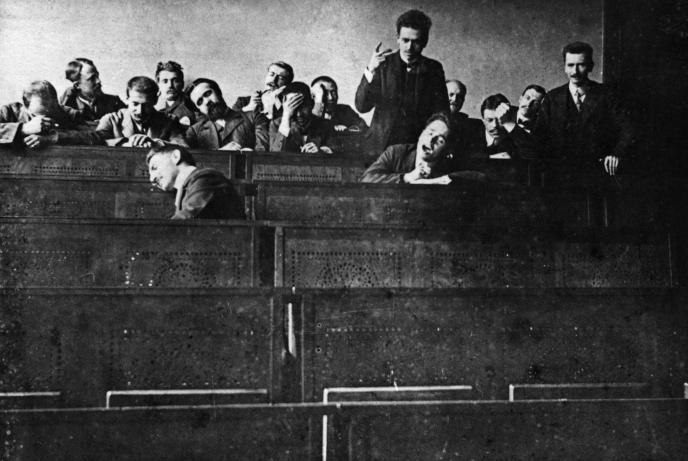

02: “Parody Photo: The Colloquium.” At the Institute for Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry at the Technical University of Karlsruhe where Fritz Haber worked and taught in 1909. Even scientists who achieve important breakthroughs have some fun sometimes. Source: Archive of the Max Planck Society, Berlin-Dahlem, Jaenicke and Krassa Collections, Picture Number VII/5.

Achieving a Scientific Breakthrough: Communicating Perspectives

Scientific discovery is a human social achievement. Fritz Haber worked on the ammonia problem from 1903 to 1909 and, though he is credited with the discovery, he did not work alone. His achievement was dependent on the successes of others, primarily the physical chemist Walther Nernst, but also Wilhelm Ostwald, who made his own unsuccessful attempts to synthesize ammonia. Archival letters between these scientists, as well as their remarks in their publications on ammonia, document how progress was dependent on communication.

One episode is particularly exemplary: the Meeting of the Bunsen Society in Hamburg in 1907. The event has become quite famous in popular writing and academic literature in the history of science. The meeting is commonly cased as a dramatic showdown between the senior scientist Walther Nernst from Berlin and the junior scientist from Karlsruhe Fritz Haber as they rushed to establish an industrial-scale method of manufacturing ammonia. It is often repeated in historical interpretations that Nernst lambasted his less experienced colleague and actually dictated which experiments Haber should perform to achieve the breakthrough.

It is possible, however, to interpret these events in another way. Rather than a humiliating smackdown, it can be seen as a robust, professional exchange. Haber, while arguably more diplomatic than Nernst, was no less pointed in his remarks on ammonia synthesis. By 1907, Haber was confident in his results and countered Nernst’s skepticism with his own convincing evidence. The “polemic” between Haber and Nernst is actually a prime example of the kind of communication between scientists that is essential to generating new knowledge. The dynamic is still alive in research today. No one person commands a complete set of scientific information and a breakthrough depends on different contributions even when they come from seemingly opposing sides.

From Science into Society: The Energy Transition in the Twenty-First Century

These complex social interconnections are at work today, not only in research itself but also within society at large. We also see increasing discourse around social inclusion compared to Haber’s time. Technological solutions certainly influence society, but broader collective decisions eventually impact science and technology as well and become, in turn, increasingly decisive within research itself. Through this mutual influence, social discourse can identify ways to respond to current and future global challenges, such as climate change and the energy transition.

03: Transporting a high-pressure ammonia reactor (oven) in 1969. The size of the pipes had remained similar since Haber’s invention was upscaled 60 years earlier. Source: BASF SE, Corporate History, Ludwigshafen.

As it happened, social discourse wasn’t imperative for the industrialization of Haber’s breakthrough. With the onset of WWI, the importance of ammonia, as a central ingredient in fertilizer and explosives, made it a vital resource for both combat and preventing wartime hunger. The technology was implemented on a global scale.

But energy transitions are not normal technological transitions. They are often long and convoluted undertakings. For the current transition, scientists and engineers are actively developing solutions towards clean energy systems, such as solar cells and wind turbines. But it is achieving social consensus and change around if and how to implement these solutions that has proven more difficult. Achieving unity within and between science, technology, and society is a central challenge of the climate and energy crises. A next step could be for researchers across the natural sciences, social sciences, and humanities to look beyond their usual work and engage in communication with society. Developing a harmonious vision of the future in this way could be the key to establishing the trust we need to solve today’s global challenges.

04: Left: An off-shore windmill produces electricity from the movement of air. Right: A solar, or photovoltaic, cell converts sunlight directly into electricity. Both are central to the current energy transition. Source: Unsplash.