How many steps have you taken today? How many calories did you burn? Is your smartwatch buzzing again to remind you to rise from your desk and get some exercise? Wearable technology, in the form of smart watches or fitness trackers, is familiar to most of us, and has become part of daily life. According to Forbes Magazine the worldwide wearable technology market will double in the coming years, with 149.5 million shipments expected in 2021. The technology’s rise illustrates the importance of quantitative assessment for our society, especially with regard to health issues, revealing how deeply integrated it has become in our everyday lives.

Fig. 1: Apple Watch. Source: Wikimedia Commons

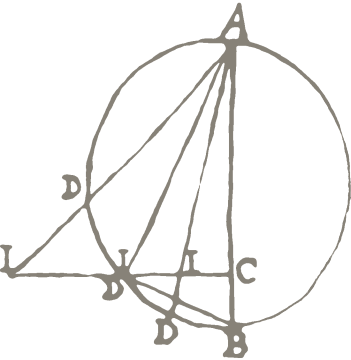

This practice of “self-quantifying,” however, is not as new as it might seem. In fact, we can trace its origins back to the turn of the seventeenth century. During this time, the physician Sanctorius Sanctorius developed instruments (Figs. 2 and 3) to measure and to quantify physiological change. In doing so, he introduced quantitative research into physiology and thus laid the foundation for self-tracking, or self-quantifying, technology.

Fig. 2 (left): Reconstruction of a pulsilogium of Sanctorius found at the University of Padua (Biblioteca medica Vincenzo Pinali antica dell'Università degli Studi di Padova). This instrument serves to measure the pulse frequency. The illustrated replica was part of an exhibition held in 1961 at the University of Padua by Loris Premuda. © Philip Scupin

License: CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 International

Fig. 3 (right): Other pulsilogia of Sanctorius. See: Sanctorius Sanctorius (1625), Commentaria in primam Fen primi libri Canonis Avicennae. Venetiis: apud Iacobum Sarcinam, pp. 22; 78. Source: © British Library Board (General Reference Collection 542.h.11, pp. 22; 78).

Historical accounts of Sanctorius and his work tend to tell the story of a genius who, almost out of the blue, invented a new medical science that profoundly influenced modernity. This new science is identified as iatrophysics, iatromechanics, or sometimes iatromathematics. These terms by no means constitute clear categories, rather being flexible appellations that have been applied retrospectively to developments in medical and natural philosophical research. The terms are nevertheless comparable: all of them reflect the importance of measurement and quantification in medical research, as well as the tendency to utilize numerical values and mechanical aspects in the field.

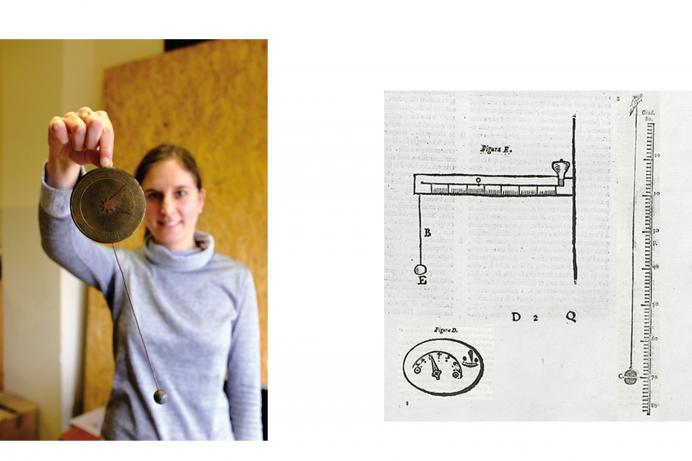

The aim of my project, “The Emergence of Iatromechanical Medicine,” is to reconsider this “genius narrative,” examining Sanctorius and his work in the broader perspective of processes of knowledge transformation in early modern medicine. Conventionally trained at the University of Padua, Sanctorius developed his quantitative approach within a mathematical tradition originating in Galenic medicine, the leading medical authority of the time. Rather than breaking with this tradition, Sanctorius integrated his novel ideas into this intellectual framework. This is best illustrated by the fact that he published all of his instruments in a commentary on Avicenna’s Canon (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4: Sanctorius Sanctorius (1625), Commentaria in primam Fen primi libri Canonis Avicennae. Venetiis: apud Iacobum Sarcinam, pp. 305-308. Source: © British Library Board (General Reference Collection 542.h.11, pp. 305–308).

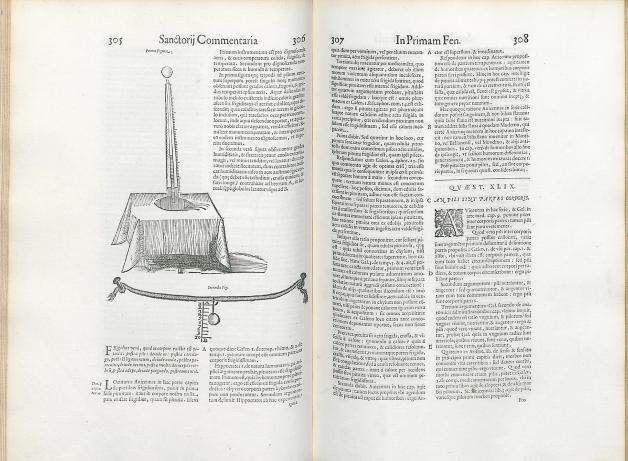

According to Sanctorius, the constant supervision of bodily excretions was essential for the preservation of health. In keeping with the classical view, he conceived of health as an ideal balance between ingestion and excretion, meaning that the quantity of food ingested should be proportionate to the amount of liquids discharged by the body. To monitor these processes, Sanctorius developed a special weighing chair (see Fig. 5).

Fig. 5: The Original Illustration of the Sanctorian Chair, see: Sanctorius Sanctorius (1625): Commentaria in primam Fen primi libri Canonis Avicennae. Venetiis: apud Iacobum Sarcinam, p. 557. Source: © British Library Board (General Reference Collection 542.h.11, p. 557).

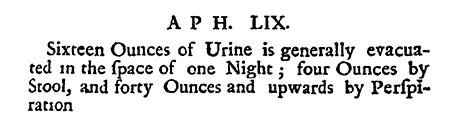

The measurements Sanctorius conducted demonstrated that a large part of excretion occurs invisibly through the skin and lungs. Referring to the medical authorities of Hippocrates and Galen, Sanctorius conceived of this so-called perspiratio insensibilis as an imperceptible excretion of moisture through which the body rids itself of harmful and polluting matter through the pores of the skin. In his view, its monitoring by means of systematic weighing was fundamental for the preservation of health. In 1614, he published the results of the weighing procedures in his most famous book entitled Ars […] de statica medicina (On static medicine). He described his observations in sayings such as below (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6: Santorio, Santorio; John, Quincy (1712): Medicina statica: Being the aphorisms of Sanctorius. London: ECCO Print Editions, p. 31.

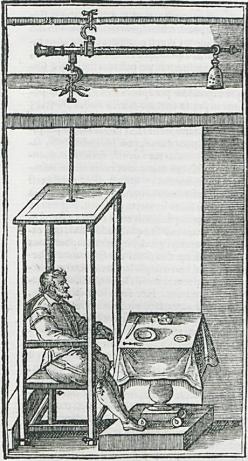

But how did Sanctorius manage to weigh the perspiratio insensibilis with such precision? Despite the balance being one of the oldest measuring instruments, most probably invented during the Neolithic period, Sanctorius was the first to have applied it to humans. To understand the functioning of the instrument and the practical and mechanical knowledge needed for this novel application of scales, Sanctorius’ weighing chair was reconstructed and experiments carried out (see Fig. 7).

Fig. 7: The Reconstruction of the Sanctorian Chair. © Paul Weisflog

In the frame of a seminar at the History of Science Department at the Technical University of Berlin, students were involved in the reconstruction process and testing of the chair. Based on these experiences, the replica was further adapted and improved. This version was exhibited at this year’s Lange Nacht der Wissenschaften in Berlin to enable visitors to try the measurements. Students and visitors helped to analyze Sanctorius’ practice of weighing, its feasibility, and the social dimensions involved in this undertaking (e.g., how many people are needed to realize the weighing experiments).

Fig. 8: Visitors at the Lange Nacht der Wissenschaften 2018. © Stephanie Hood.

From the written sources of Sanctorius we know that his use of the balance was two-fold: on the one hand, it functioned as a research tool to monitor variations in the production of perspiratio insensibilis. On the other, it helped to determine and maintain an ideal body weight. According to Sanctorius, a healthy amount of food was directly connected to the quantity of the perspiratio insensibilis, as the quantity, quality, and type of food and drink affected the expulsion and retention of the sensible and insensible excretions.

The experiences with reconstruction suggest that Sanctorius adapted the measuring method with regard to these two different functions. It seems likely that Sanctorius tried to define the healthy quantity of insensible perspiration in an initial phase. As soon as he managed to stabilize this quantity, he might have realized that the chair not only helped the physician to monitor changes in weight and, on this basis, to issue rules of health, but also offered the opportunity to find and maintain an ideal weight. In order to enable individuals, even laymen, to use the chair on their own, he might have used a different measuring method and adapted the design of the weighing chair accordingly. This could also explain why Sanctorius published the description and illustration of the weighing chair only 11 years after the De statica medicina, in the commentary on Avicenna. When he discovered the new function of his weighing chair, he might have felt the need to publish the instrument in order to make it accessible to a broader audience.

Soon after their publication, Sanctorius’ weighing chair and the De statica medicina “went viral” all over Europe, even reaching South Carolina in Colonial America. Many scholars imitated the weighing experiments, and were excited about Sanctorius’ novel idea and method of quantification. In 1711, a reader of the English periodical The Spectator described his method of using the “Sanctorian chair”:

“Having provided my self with this Chair, I used to Study, Eat, Drink, and Sleep in it; insomuch that I may be said, for these three last Years, to have lived in a Pair of Scales. […] As soon as I find my self duly poised after Dinner, I walk till I have perspired five Ounces and four Scruples; and when I discover, by my Chair, that I am so far reduced, I fall to my Books, and Study away three Ounces more.” (Bond, Donald F. (ed.) (1987): The Spectator, Vol. 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 106. First published in 1711.)

Just as we use today’s wearable technology to decide whether we help ourselves to a big slice of chocolate cake (or not), Sanctorius’ weighing chair was used to maintain an ideal weight. It could be argued that it paved the way for our quantified selves.