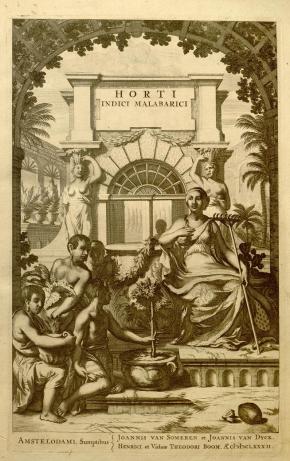

The most famous of their fine-grained experiential descriptions of plants is a 12-volume herbal cataloguing medicinal uses of plants, the Hortus Indicus Malabaricus (“Malabar Garden”), on the plants of a part of southwest India (the modern state of Kerala), published in Amsterdam between 1678 and 1693.01

Despite the importance of the Malabar Garden for early-modern natural history—the naturalist Linnaeus described 100 plant species based on it—and modern botanical taxonomy, very little historical research has been done on it. My project studies the Malabaricus along two axes using the conjoined methodologies of archival and ethnographic research. First, I study it as a product of Dutch colonial natural knowledge-making, examining its visual culture, its use of indigenous plant names, and the ideas of experience embedded in its plant descriptions. Second, I explore its cultural and political importance in Kerala today as a putative source of information on lower-caste healing practices. The Hortus Malabaricus is a hotly-contested piece of intellectual property in Kerala, and members of the state’s Ezhava community insist that the knowledge contained in its volumes is theirs and theirs alone.

01. Frontispiece, Hortus Malabaricus. Source: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/14375#page/4/mode/1up

The Wondrous Visuals of the Hortus Malabaricus

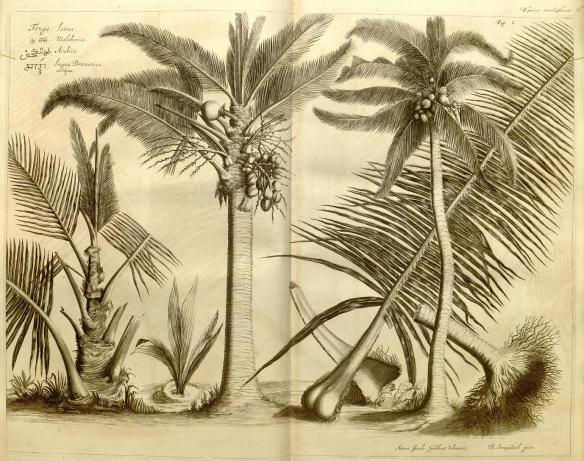

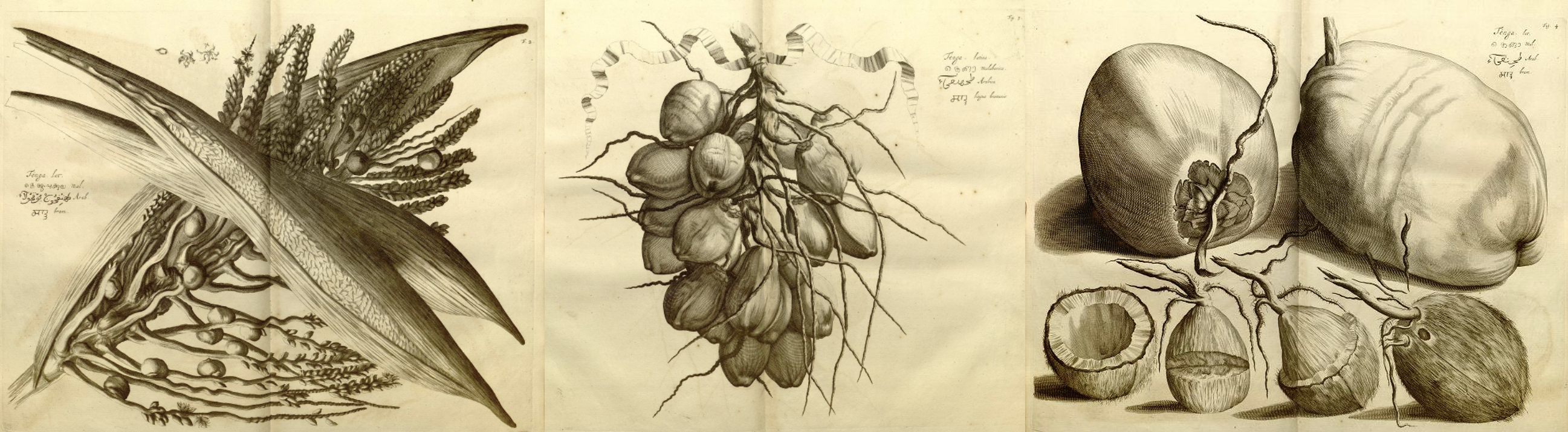

The Malabar Garden is a wondrous creation. Sprawled across its double-folio pages are stunning representations of “exotic” nature, lovingly conjured in exquisite detail. Consider the images of the Tenga (Cocos nucifera L.) with which the first volume opens. The full-grown palm with its sinuous trunk and waving fronds; the tree at different stages of its growth; the mature tree, a frond dramatically represented, diagonally stretched across the page—a persistent feature of the images, quite different from the European visual idiom of the time.02 Visual documentation in the Malabaricus shows branches truncated to clarify plant structure, and sophisticated sequencing techniques in which images on successive pages represent a “zooming” process that ends with “close-ups” or dissection of fruit or seeds, making comparisons easy.03

02. Tenga (Cocos nucifera L.) from Hortus Indicus Malabaricus Volume 1

These two pages depict the Cocos nucifera L. at different stages of its growth—the young palm emerging from the pit dug to receive the drupe, from which the new plant grows; the development of its fronds; the sturdy young tree with a toddy tapper’s pot attached to the stem. (Left) On the right-hand folio, the mature tree with a frond diagonally represented behind it.

What does the Malabaricus represent as a visual corpus? It appears to closely follow European conventions of natural scientific representation—with a twist. Its diagonal images and black-and-white engravings appear specific to depictions of naturalia in European colonial settings, inviting research and comparison with manuscript and printed illustrations produced in other colonies, such as in South East Asia. Hendrik Adriaan van Reede tot Drakenstein (1636–1691), the Malabaricus’s creator, recorded his obsession with sensuous minutiae: “There will also be people who find it tedious that in the descriptions of the plants there are so many minor details, on which indeed we have bestowed the greatest care” (Preface, Volume III). We can see that van Reede’s experience and experiential knowledge making enter the making of the images, as he supervised the collecting of plants, observing, touching, and tasting them.

03. Two plates following each other in Volume 1 show a bunch of flowers with florets at varying stages of growth—buds, newly-opened flowers, young fruit, and an inset showing details of the developing ovary, calyx, and petals. The third plate shows the immature coconut fruit in its green outer casing followed by close-ups of the mature drupe with and without its hard, inner casing.

The Textual Descriptions of the Hortus Malabaricus

But what of the textual descriptions? The rationale behind these is hinted at by an order issued by the VOC to its functionaries in Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and the Coromandel (southeast India) instructing them to study medicinal plants to avoid importing drugs from the Netherlands. Despite this, the images reveal little about the medicinal qualities or therapeutic uses of the plants. The text of the Malabaricus, though certified as authentic knowledge by three Brahmin physicians, Ranga, Apu, and Vinayaka Bhatt, shows no familiarity with theories associated with classical Ayurvedic medicine, nor are the Sanskrit names of plants recorded. The names of plants found in the Malabaricus are in Malayalam and Konkani (languages of southwest India), polygraphically represented in Nagari, Malayalam (kolezuthu), Arabi-Malayalam, and Roman scripts.

This raises the question of whose knowledge the textual descriptions convey. Many plant descriptions mention their use as antidotes for animal and plant poisons. Malabar was well known for various traditions of viṣacikitsā (“treatment of poisons”), caste-specific knowledge practices, which the Dutch picked up during their time there. The inclusion of such “local” knowledge is attested to by a series of testimonials gathered from native knowledge bearers as printed in Volume I. Among them is a certificate from an Ezhava physician named Itty Acchudan testifying to the accuracy of the information he imparted to his Dutch interlocuters:

“I, Itti Achudem, a Malabari Doctor … testify that I came to the City of Cochin as per the order of Governor Henry A. Rheede, and … told and dictated names, medical powers and properties of plants, trees, herbs and creepers, written and explained in our book and which (plants) I had observed by long experience and practice…”

The Public Life of the Hortus Malabaricus in Kerala Today

In 2003, a distinguished Ezhava botanist, K.S. Manilal, published an English translation of the 12 volumes of the Malabaricus. Through Manilal’s translation, the Ezhavas, a historically low caste, became identified with sophisticated medical and botanical knowledge. In the years between the publication of the English translation and today, Ezhava activism around the Malabaricus in Kerala has assisted the growth of a public understanding of it as the cultural property of the Ezhava community. This has expressed itself institutionally, for example, in the creation of a “Hortus Valley” at the Malabar Botanical Garden and Institute for Plant Sciences in Calicut in north Kerala, where 432 of the Malabaricus species appear, each in its own plot, accompanied by a plate with its Malayalam and modern botanical names and a description of its medical uses.

The cultural meaning of the project is strikingly presented in the design of the ornamental gateway to the valley, which re-creates the frontispiece of the Malabaricus as a bas relief. Here the caryatids of the original etching are replaced by an Ezhava couple, who bear the weight of the book’s title, with an image of Itty Acchudan in place of the goddess of Indian botany. Acchudan holds a palm leaf manuscript in his right hand, and a conch shell container for medicament in his left.04 The meaning of the representation could not be clearer: the knowledge contained in the Malabaricus belongs to the Ezhavas…

04. Photo, gateway to the “Hortus Valley” at the Malabar Botanic Garden. Ezhava physician Itty Acchudan is depicted in the center of the gate. Source: Minakshi Menon.

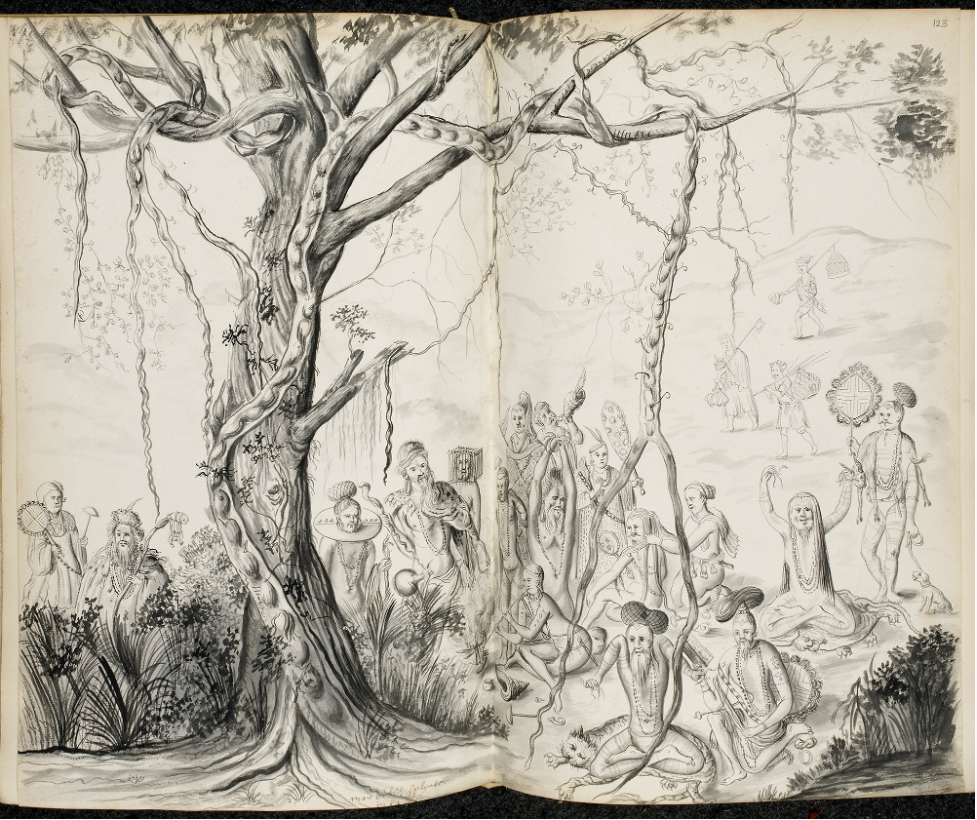

05. A gathering of faqīrs. This unpublished drawing by one of Van Reede’s draughtsmen, Marcelis Splinter (n.d.), gestures at the Malabaricus’s Indian Ocean world connections. Faqīrs (literally, “paupers”), Sufi mendicants, were sometimes indistinguishable from Hindu yogis. They were itinerants, often learned in medicine, who wandered the port-towns of the Indian Ocean, healing the sick and instructing students. European sources of the period sometimes refer to them as “snake charmers”(notice the faqīr holding a snake). Source: Horti Malabarici Icones. BL Add MSS 5030: 122–123.

04. and 05. Click the image to see both images and captions.