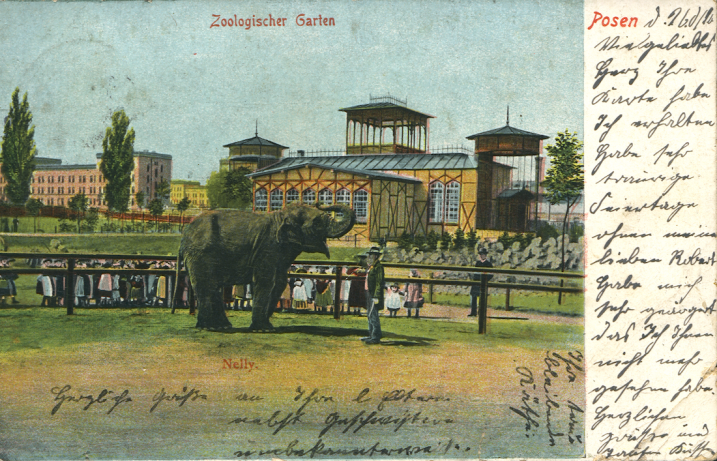

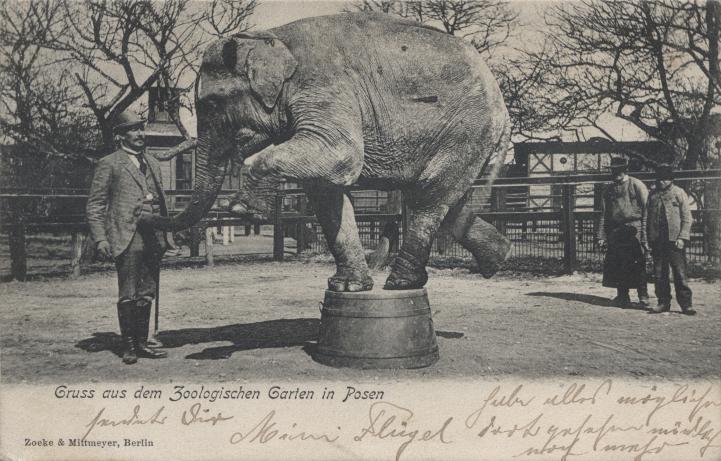

Postcard featuring Nelly, the first elephant in the Poznań Zoological Garden (Poland) displayed between 1895 and 1907. Source: Poznań University Library Archives.

Elephant Extinction and the UK Ivory Bill

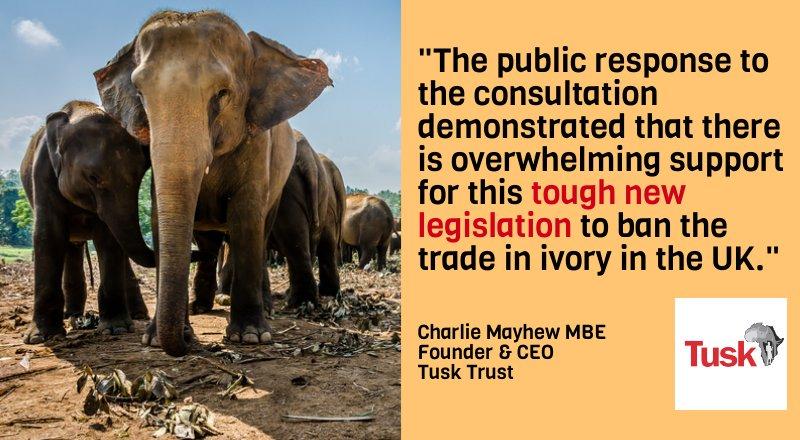

According to the World Wildlife Fund, the population of African elephants (Loxodonta africana and L. cyclotis), declined from three to five million in the nineteenth century to approximately 415,000 today, largely as a result of hunting. Wildlife conservationists point to a surge in poaching for ivory in recent years: it is estimated that 35,000 elephants are killed illegally each year for their tusks. In 2013, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) named China as the main destination for ivory illegally trafficked from Africa. Meanwhile Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) are classified as endangered, with fewer than 50,000 left in the wild. In response to this decline the United Kingdom passed a new law in December 2018 that prohibits the sale or purchase of any objects containing ivory, regardless of their provenance or age. While international trade in ivory has been strictly forbidden since 1990 under CITES, this domestic measure is the most restrictive ban on ivory trade in the world to date. It aims at curbing the commercial demand for ivory products, in doing so protecting wild elephants. As the new rules come into force in 2019, the UK’s total ban on ivory has incited heated debates on animal rights and wildlife conservation, as well as cultural heritage and the colonial legacy of museum collections.

Statement by Defra UK on the ivory ban implemented in 2018. Source: Defra UK.

Ivory as a Global Commodity

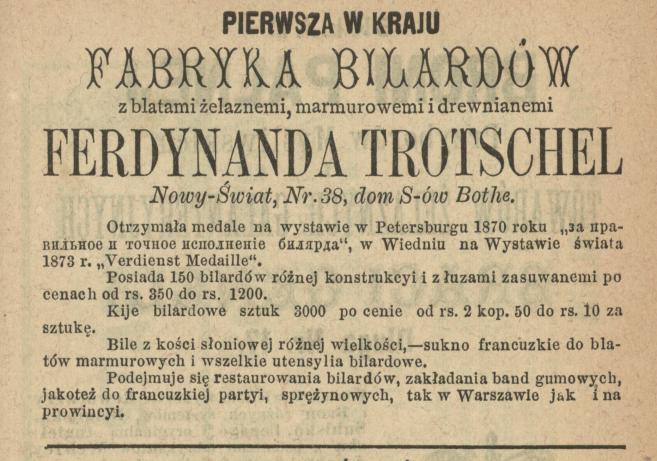

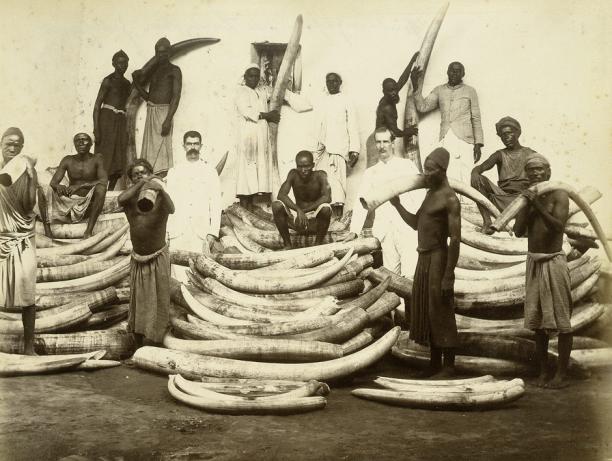

For centuries ivory was a global commodity, shaping material cultures beyond elephant habitats. This highly prized material comes from the tusks and teeth of several animals: elephants, hippopotami, walruses, warthogs, sperm whales, and narwhals, as well as extinct mammoths and mastodons. However, ivory from elephant tusks—incisor teeth—is considered the most valuable due to its large size. Why is this dental tissue so cherished across different cultures? Associated with purity and chastity due to its whiteness, ivory was aptly used in Christian devotional art. As a craft material, it is valued for its durability and easiness to carve in fine detail. Artifacts such as carved figures, tools, musical instruments, and weapons made with the use of ivory fill the shelves and storage rooms of museum collections. Before the introduction of plastic, ivory was also widely used in manufactured everyday objects like cutlery handles, billiard balls, piano keys, buttons, jewelry, and other decorative items. The piano industry only abandoned ivory as a key covering material in the 1970s in the United States, and not until the 1980s in Europe. But the demand for ivory was at its peak far earlier, during the late nineteenth-century Scramble for Africa. The close relationship between trades in slaves and ivory renders the so-called “white gold” not only a colonial commodity, but also a symbolic object engendering specific imaginaries of European whiteness.

Advertisement for the first Polish manufacture of billiards offering ivory billiard balls. Source: J. Nosowski, “Illustrated Guide to Warsaw.” 1880. p. 51.

The Value of Ivory

The high value of ivory material can be associated with the fact that it is derived from the largest land mammals that fascinated humankind for millennia. The first elephants brought to European courts as diplomatic gifts for popes and kings served as tokens of power and influence. These rare and wondrous creatures were among the most treasured exotic live cargo. Since the fifteenth century the display of elephants had mediated multiple meanings and desires connected to their places of origin, and prompted imaginations and longings about those distant geographies. In his influential Histoire naturelle (1764), Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon wrote that the elephant “is the most respectable animal in the world. In size he surpasses all other terrestrial creatures; and, by his intelligence, he makes as near an approach to man, as matter can approach spirit.”

Ivory trade, East Africa, 1880s/1890s. Source: www.bassenge.com

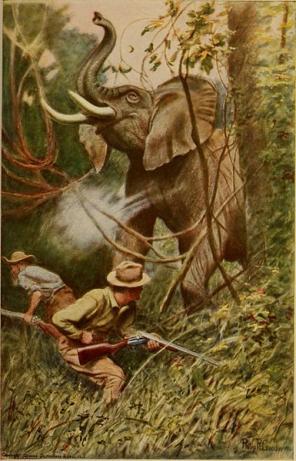

In the twentieth century, white trophy hunters also praised elephants as the ultimate game. In his African Game Trails (1910), Theodore Roosevelt wrote:

“No other animal, not the lion himself, is so constant a theme of talk, and a subject of such unflagging interest round the campfires of African hunters and in the native villages of the African wilderness as the elephant. Indeed, the elephant has always profoundly impressed the imagination of mankind. It is, not only to hunters, but to naturalists, and to all people who possess any curiosity about wild creatures and the wild life of nature, the most interesting of all animals.”

Image from African Game Trails by Theodore Roosevelt, 1910. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Postcard from the turn of the twentieth century featuring an Asian elephant performing in front of an audience. Source: Poznań University Library Archives.

East and West

This enduring fascination with elephants turned their bodies into colonial trophies, dead or alive. While captive elephants were the hallmarks of European zoological collections, ivory became a luxurious commodity and an expression of wealth. At the turn of the twentieth century, patterns of ivory consumption were closely connected to the growing middle-class in Europe and the United States. As a status symbol ivory signaled elevation in social rank, especially for those whose belonging to European culture or even whiteness was in doubt. Thus, recording consumer desire for ivory in Eastern Europe, a region that, on the one hand, largely “missed out” on securing its own African or Asian colonies, but one that nevertheless nurtured colonial longings, reveals close links between social constructions of race, colonial commerce, and animal bodies. For the region caught between the constructions of “progressive West” and “backwards East,” the elephant body served as a material link between the mystical Orient and the colonial Empire, and helped to measure the differences of savagery and civilization.

A pair of porcelain perfume bottles placed on an ivory stand. First half of the nineteenth century. Source: RDW MIC, Virtual Małopolska project/Wirtualne Muzea Małopolski.

Pair of ivory perfume bottles with a floral pattern, latter half of the 19th century. Source: Wirtualne Muzea Małopolski, Katarzyna Sosenko.

Pair of ivory perfume bottles with a floral pattern, latter half of the 19th century. Source: Wirtualne Muzea Małopolski, Katarzyna Sosenko.

Pair of ivory perfume bottles with a floral pattern, latter half of the 19th century. Source: Wirtualne Muzea Małopolski, Katarzyna Sosenko.

Pair of ivory perfume bottles with a floral pattern, latter half of the 19th century. Source: Wirtualne Muzea Małopolski, Katarzyna Sosenko.

Pair of ivory perfume bottles with a floral pattern, latter half of the 19th century. Source: Wirtualne Muzea Małopolski, Katarzyna Sosenko.

Pair of ivory perfume bottles with a floral pattern, latter half of the 19th century. Source: Wirtualne Muzea Małopolski, Katarzyna Sosenko.

Pair of ivory perfume bottles with a floral pattern, latter half of the 19th century. Source: Wirtualne Muzea Małopolski, Katarzyna Sosenko.

Pair of ivory perfume bottles with a floral pattern, latter half of the 19th century. Source: Wirtualne Muzea Małopolski, Katarzyna Sosenko.

As part of Department III’s research theme “The Body of Animals,” this project offers a unique insight into a physical presence of colonial imperialism in an area without overseas colonies. Tracing elephant lives, deaths, and afterlives, all entwined with stories of their keepers, trainers, and veterinarians, uncovers a variety of scientific practices and technologies behind the exotic animal trade. A focus on one species allows to explore the complexity of traffic in exotic species operating within a network of institutions like zoos, circuses, and traveling shows, as well as commodity chains that seemed to belong to the past, but are revived in the present.